The thing about this photo in the New York Times from the US campaign trail is that Biden no longer looks anything like Biden. Can someone explain this to me? Is it Photoshop? Some intern on overtime at Madame Tussaud’s? Or has the inevitable already occurred and he’s morphed into an octogenarian lizard lord with a perma-tan? Whichever, he is not fit for office, let alone another term no matter what fantasy the Democrats continue to cultivate. The experienced middle-class white man was always going to be the safer bet over his female side-kick, though. Then there’s Harris who isn’t all that far off Biden in that listening to her for more than a few minutes inculcates a generous portion of blancmange in between your ears. It is truly baffling that in a nation with a mass populace of 333.29 million people, the best universities in the world and the highest amount of tech geniuses, we can be left with the prospect of either Biden or Trump, again. Trump did not materialise out of nowhere though, he is a mirror of American society. He also promises to get the price of a tank down.

Moving on, a fellow PGR recently asked me in an informal sharing session at her place, on listening to my track “Dream Catcher”1 (E), which I’m screening in various formats, including the KISMIF DIY conference in Porto, Portugal, in July, how I accounted for the ‘blackness’ in my music.

It’s not an easy question to answer. I suspect it has seeped in via osmosis. I also advocate oral cultures, being a songwriter who doesn’t write anything down. More to the point, as we are, all of us, cracked vessels, I suspect it correspondingly seeps out. And when it comes to the blues, the one man band singing about ‘love gone wrong’ on a busted guitar and fashioning a space of freedom before getting back to the grind was always singing about someone else or some place else—for the blues is nothing if not a nomadic form.

We are polyphonic creatures. It is never only us that comes out of us. Black music comes from pain and trauma and solidarity. Field hollers and work songs which came about during slavery and the civil war (1600-1900) harnessed collective muscle-memory, giving rhythm to labour, and labour to rhythm. They were not only a practice of but a demand for, freedom. Perhaps, when we sing, all the music we have ever heard is running through us all at once and whatever noise we make is us + that. We sing from experience and we need experience to sing.

That may account for her question.

But what is running through us when we sing?

The Dutch philosopher and lens grinder, Baruch Spinoza2 would have said spirit, some would say culture.

In Bento’s Sketchbook (2011), John Berger raises the question of where the impulse to draw comes from. He then endeavours to answer this by homing in on Dutch philosopher, Baruch Spinoza’s God is nature itself, via an investigation into drawing, politics and storytelling. For Spinoza, God is present in the act of drawing, in the single-handed gesture, and therefore in the line, as much as he is in the beauty of a flower or the blueness of the sea, for example. Similarly, D. H. Lawrence’s modernist novels deal not only with the contemporaneous sense of social isolation experienced after the industrial revolution but sexuality, the unconscious, or blood-consciousness, and our sense of what it is to be rooted to the Earth, to experience, in his poems.3

His sensibility to life was one of embracing spontaneity in order to be fully alive. It then follows that for Lawrence (as with Spinoza) God is always looking for a body. We see an example of this inclination in his novel Sons and Lovers (1913)4 when Paul Morel is speaking to Miriam: “It’s not religious to be religious … I reckon a crow is religious when it sails across the sky. But it only does it because it feels itself carried to where it’s going, not because it thinks it is being eternal” (p.479).

It is often described by songwriters that they are an antenna for the music. In my recent Annual Performance Review, I said: “I am not in control of it [the practice/writing songs], and I wouldn’t want to be.”

Such a focus on ‘receptivity’, over ‘creativity’, would account for that all too common sensation cited in the literature by songwriters (Flanagan, 1987; Zollo, 2020)5, and experienced when listening back to recordings one has made, which tends to be one of surprise: Where did that come from? Or was that even me?

Emphasising the role of ‘active surrender’ in art, Brian Eno puts it so: “All I’m ever trying to do is to make something magic. Something that makes me think fuck, isn’t life amazing. That’s all I want” (British Council Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2018, 00:49:18).6

It’s gone nine. The vertical blinds are blowing. I should shut the door. The delete key is doing that thing where it keeps going long after you’ve let go. I am flicking between editing this page, and Emerson’s “Experience” (1842)7.

In “Experience”, Emerson called upon us not to over intellectualise life. He stresses that it is our personal experiences that forge us, not what we read or absorb of other’s ideas. He also implores us to live life as an experiment. “So in this great society wide lying around us, a critical analysis would find very few spontaneous actions. It is almost all custom and gross sense” (Emerson Central, 2024, p.3)8.

The night time lights on the grass via the extended walkway have been turned on. The sound of several years of construction work has gone. The munroes are just about visible, beside the new build. The non-stop drilling from the shipyard, (which I pointed my condenser mic at and tried to record, thinking I’d turn it into a drum beat), has ceased.

“All things swim and glitter” (quoted in Emerson Central, 2024, p.2).9

Boatright (2023) critiques the process of reading Emerson as a “transformative” experience through which Emerson calls upon us to embrace the concept of experience as a means through which to remain open to life, serendipity, and spontaneity, through which we come to knowledge.

Professor Cornel R. West recently delivered his 2024 Gifford Lectures10 at the University of Edinburgh. This incomparable series, entitled: ‘A Jazz soaked Philosophy for out Catastrophic Times: From Socrates to Coltrane’ was quite sensational and unlike anything I have ever witnessed in a lecture hall. West is a not only a staggering intellect and a deeply spiritual thinker but also a charismatic musician and spoken word artist who is able to captivate an audience and hold them spellbound, over hours, without losing momentum. His compassionate, learned and free-wheeling, even preacher-like, style is steeped in oral culture. One doesn’t so much watch him as witness him. The attention he commands is palpable even via a tiny screen. Everyone in the audience knows that they are a part of something they will never forget.

Roaming luminously through Plato, to Shakespeare, to Montaigne, to Vico, to Nietzsche, to Emerson on where we find ourselves, to Woolf, to his compatriot, the late bell hooks, who bonded in their mutual aim to expose class and racial injustice, both being that rare breed of academic unashamed to put love at the centre of their discourse, he is the converse of death by PowerPoint.

What are we seeing with West, though? Is it a lecture series, a performance, an oral testimony or a form of prophecy? (Prophecy and accuracy being different registers, as he points out.) He boomerangs through the catastrophic, the existential, and the pedagogical via an entirely idiosyncratic and peripatetic exploration of free jazz, blues/swing, and improvisation—anchored to Coltrane. Neither is he uncritical of current ideologies, trends, and bandwagons. In the Q&A, for example, he takes some umbrage with EDI (Equality, Diversity and Inclusivity) initiatives11, stressing the point that “decolonising the curriculum” really depends upon who is doing the decolonising. This resonates with Varoufakis’s reminder in Technofeudalism (2023)12 that the problem with algorithmic culture is not what they know about us, but who knows what, for this is where the power lies.

The highlight of the Gifford Lectures 2024, at the end of lecture six - ‘A Love Supreme (A Way Through)’ brought on a warmth in the auditorium over an intellectual epiphany. The standing ovation had me wondering if West was going to do an encore. Instead, he began chanting: “A love supreme, a love supreme…”, and laughing, bringing the audience with him. Such moments of collective transcendence get born out though rituals such as sport, stadium gigs, and so on yet rarely in a lecture hall.

Eno touches upon a similar transcendent experience that profoundly affected him, which he describes in a lecture at The University of Edinburgh (2017, 01:34:22) as the most profound musical encounter of his life. It was that of being sung to by a Gospel congregation whilst living in California despite being a committed atheist, he states:

When you join a gospel choir what you do and the pleasure of what you do is that you surrender. You stop trying to be in control. Now we live in a culture that has got where it is by being able to control nature.

He also cautions us that this is the same impulse which leads to fascism.

I recently gave a talk at the university’s Music symposium. I was going to present my video essay The Path of Totality based upon my compulsive online excursion into watching clips on YouTube of the recent Great North American Eclipse which coincided with receiving the custom Blackout Baby EP from the cutters. Symbolically, the record resembled the eclipse (it was black and round!) and my ideas tend to come visually. But the resulting video essay exceeded the conference format in duration so the convener asked if I would be happy to show only a part of it, to leave time for the Q&A. Eh? He wanted me to cut up this dark Romantic piece on totality? No way!

A Love Supreme13 is considered Coltrane’s masterpiece. It is also a statement of his spiritual recovery. He had one of the best jobs in jazz, touring with the Miles Davis band. Yet, substance-fuelled, his playing swung from the jaggedly brilliant, to the demonstrably numb. Davis understandably fired him. Coltrane’s band mate, the pianist, Mccoy Tyner, (Westervelt, 2012)4 sums up this time as one of risk and spontaneous rapture:

I couldn't wait to go to work at night. It was just such a wonderful experience. I mean, I didn't know what we were going to do. We couldn't really explain why things came together.

The chant14 came out of Coltrane’s solo in the opening part “Acknowledgements” (the others were “Resolution”, “Pursuance” and “Psalm”), through variations upon a simple four note motif, which he repeats 36 times.

When West reimagines this for a 21st century audience in an auditorium, then, he single-handedly abolishes bloodless managerialism and encroaching neoliberalism, ushering in an uncommon, communal joy. This is no easy fate. Neither is getting people from the U.K. to sing in a lecture hall, or anywhere, impromptu. He brings home our business as temporal creatures, our historical consciousness stamped upon us thorough a rich legacy of European philosophical discourse, whilst acknowledging indigenous plurality, and, of course, Marx—in that we continue to shape the world but not under conditions of our choice.

Segueing to Aretha Franklin, West mentions “Amazing Grace”15 a song not written by a Black musician but by an English slave trader called John Newton (1725–1807) who converted to Christianity and then repented of his previous exploits in the slave trade. Even so, Franklin makes this song her own. The album of the same name was recorded live at the L.A. Missionary Baptist Church in 1972. I sought it out on YouTube.

You can hear the room sounds and the anticipation of the congregation, with their clapping, gasping, and whooping—hanging on her every note. With her unfathomable voice, Franklin seeks out every dark corner and crevice and drags it into the light.

Aretha’s father, C. L. Franklin, an American Baptist Minister, is also in the room. He gives a speech just over half way in, saying that she, [Aretha] “never really left the church”. The crowd erupt.

These old recordings are so rich and resonant compared to the generative AI slush we are drowning in. Yet I doubt cloning and voice recognition software will ever be able to soar, or break. One imagines Aretha, sat there, her back a little stooped. Her vocal running long and deep like a canyon river.

I was busking along the river the other night with a flute and amp when a French girl passed by. I knew she was French immediately as she had that casual beauty that only French women have. I then saw her again the next day, exercising, and she asked if that was me singing the other night. I said, yes, and she said that, along with the sun, it had “enlivened” her evening. Small things.

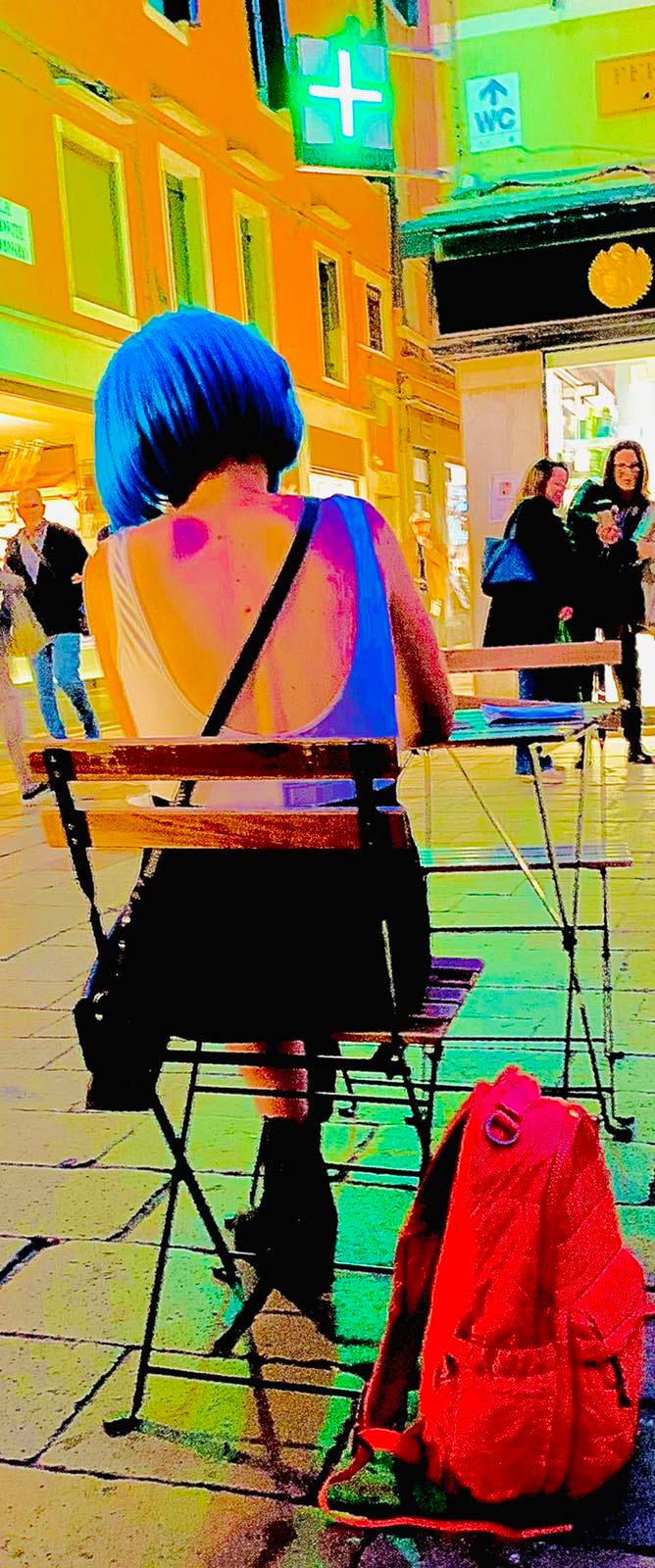

When asked what the ‘takeaways’ of what we do are, they are not always obvious, or even quantifiable. When in Venice, for example, undertaking the Space Junk Broadcast Tour in October 2022, I was given several photographs of me, taken from different vantage points on the same occasion when I was wearing my blue wig, by a night receptionist at the hotel I was staying at, and an air host on a stopover who worked for BA.

I was also given a handwritten thank you note from a South African girl who was deeply homesick, who said I was her angel, and approached many times by those curious as to what I was doing. I was told that my spontaneity invited others into their own.

When singing with my amp across The Grand Canal (footage I have not posted online) a gondola passed by with a full load of tourists. They all began to wave at me, as did the gondolier, smiling, and I waved back. It was one of the happiest moments of my life, in which I felt totally at home. None of these events could have been anticipated.

Similarly, on the more recent album launch on the Camino, my carrying the amp led to many conversations and new ‘followers’. It became a talking point on the route that there was this a female musician doing these impromptu dances with an amp on the beach. Other pilgrims stopped and took photos or video, then later in the alburgues they wanted to know my story, and why I was doing this.

Most of the routine situations we face daily call upon us to be in control of proceedings; yet, this absurd stunt, piece of performance/endurance art and act of resistance to negate the album ‘sinking without a trace’ on DSPs, was, though, a combination of two things I like to do—walk, and make art.

On The Eye of the Storm - The Political Odyssey of Yanis Varoufakis (2024), in a three-way conversation with Varoufakis and the host, Eno highlights the value of identifying what is is we like to do, and doing it.

In our reputation economy, the word ‘like’ has assumed a ubiquitous currency in a world bursting with heart emojis16. Yet, if we think about whatever it is we like doing, these things are our internal compass, or, as Eno terms it, our “lodestars” (Eye of The Storm Podcast, 2024, 00:36:23) and we need to do them. Unleashed creativity only bites back. For Eno, “active surrender” is a most unvalued proposition in art which resonates with my PhD audio statement on spontaneous song as I recorded it in 2023: Vehicles for Abandon.

He goes on to suggest (Eye of The Storm Podcast, 2024, 00:52:30-00:53:05):

surrender is the most underrated human activity. Surrender is what we do when we have sex, when we take drugs, when we engage in art, when we engage in religion. Those are all activities where we deliberately let go of some of our agency, some of our need, our obsession with control and say I’m going to let myself be controlled, I’m going to let something take me over. I’m going to become not me but part of something else.

Varoufakis, who he is conversation with, then brings up love “with the fall”17 as a complimentary type of surrender which is thwarted in the algorithmic dating ‘market’. I previously wrote on this in Cold Intimacies: Love and capitalism drawing upon the Israeli sociologist, Eva Illouz’s critique of emotional capitalism, the work of the British photographer, Jane Hilton, and feminist performance art.

Varoufakis refers to Alain Badiou’s In Praise of Love (2012) in which the French philosopher extols love as “zero-risk” and a radical contingency. Žižek draws upon Badiou to surmise that the dating ‘market’ and algorithms are returning us to pre-Romantic times or “love without the fall”, when we need the fall.

Such theory found its way by osmosis into track twenty “Freezer Delight”, on Space Junk which is a one-take fantasy set down the freezer aisle of Asda on a Thursday night, and a lyrical take on class consciousness, to quote:

“But what if I want the fall / Would you be so kind / To pick me up off the floor / To make my shoes shine?”

At the Andrew Carnegie Lecture Series which also took place at The University of Edinburgh, in 2017, Eno contends that, as is the focus of this post, that “all art is automatically political.”18 It is bound up in our method, how we make, and how we go about realising our vision. It is bound up in us. Being a musician who does not play any instruments, as such, it is rather through technology that Eno has extended himself into the world. Making work differently is, in itself, a political statement. Such notions would seem to me to be married to class, and our desire to transcend our current situation.

I wanted to leave you with this video of Silent Photography in Death Valley by Graincheck. She uses ASMR to augment natural sounds and generate atmosphere. I was drawn into her embodied and meditative process which is exceptionally calming. She seems to be creating space, and silence, and slowing down time. Although she does speak in ushered tones when promoting the sponsored Nomad bag, the most repetitive sound is that of her camera shutter. Twisting her body to get the right shot, and setting up her gear in the middle of an empty road, it’s as if she’s won the lotto. Alone in the valley, doing her thing. The stillness and calm stands out in opposition to the noise we are drowning in.

*This is a special note to say thank you to my new Founding Member, Nige Cook. Thank you Nige, your support is very much appreciated.

Next up

The Glad Cafe, Glasgow, electric guitar improvisation & vocalisation with GIOdymanics. Weds 29 May, 7:30 pm - close.

Talbot, S.L. 2023g. Dream catcher. Sam Lou Talbot. Space junk. [Online]. Glasgow: Sam Lou Talbot. [Accessed 17 December 2023]. Available from: https://samloutalbot.bandcamp.com/track/dream-catcher

Berger, J. 2011. Bento’s sketchbook. London: Pantheon.

Lawrence, D.H. 1993. The complete poems of D.H. Lawrence. New York: Penguin.

Lawrence, D.H. 2013. Sons and lovers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Flanagan, B. 1987. Written in my soul. 2nd ed. Chicago: Contemporary Books.

Zollo, P. 2020. Songwriters on songwriting. 4th ed. New York: Hatchette Books.

British Council Bosnia and Herzegovina. 2018. Artist's talk by Brian Eno. History Museum of BiH. Sarajevo. [Online]. [Accessed 22 May 2024]. Available from: https://youtube.com/watch?v=uAfx1_Bit00

Emerson, R.W. 1842. Essays-second series. Auckland: The Floating Press.

Emerson Central. 2024. Ralph Waldo Emerson. Experience. From essays: second series (1844) [Online]. [Accessed 21 May 2024]. Available from: https://emersoncentral.com/ebook/Experience.pdf, pp.2-3.

Emerson Central. 2024. Ralph Waldo Emerson. Experience. From essays: second series (1844) [Online]. [Accessed 21 May 2024]. Available from: https://emersoncentral.com/ebook/Experience.pdf, pp.2-3.

University of Edinburgh. 2024. Professor Cornel West lecture six: A love supreme (A way through). [Online]. 20 May. [Accessed 25 May 2024.] Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yhehelwF-8Y

Edinburgh Gifford Lectures Blog. 2024. 17 May. Cornel West - 'A jazz-soaked philosophy for our catastrophic Times: From Socrates to Coltrane'. [Online]. [Accessed 24 May 2024]. Available from: https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/gifford-lectures/2024/05/17/cornel-west-lecture-6-a-love-supreme-a-way-through

Equality, diversity and inclusivity. For more on this, see Sara Ahmed’s critique of diversity, through which she asks what diversity does:

Ahmed, S. 2012. On being included. Racism and diversity in institutional life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Varoufakis, Y. 2023. Technofeudalism. What killed capitalism? London: The Bodley Head.

Coltrane, J. 1965. A love supreme. [Vinyl]. US: Impulse! Records.

John Coltrane. 2018. A love supreme, pt. I - acknowledgement. [Online]. [Accessed: 22 July 2020]. Available from: https://youtube.com/watch?v=TMvbUKqWYEs

The song “Amazing Grace” was not written by a Black musician but by an English slave trader called John Newton (1725–1807) who converted to Christianity and repented of his previous exploits in the slave trade. Even so, Franklin makes this song her own.

Han, B. 2018. Saving beauty. Translated by D. Steuer. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Han, B. 2024. The crisis of narration. Translated by D. Steuer. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Eye Of The Storm Podcast. 2024. Brian Eno and Yanis Varoufakis. The most important question to ask. Podcast 3. [Online]. [Accessed May 25 2024]. Available from: https://youtube.com/watch?v=cr75x7Ql3Hk

University of Edinburgh. 2017. Andrew Carnegie lecture series - Brian Eno. [Online]. [Accessed 25 May 2024]. 19 January. Available from: https://youtube.com/watch?v=0qATeJcL1XQ