I. The Air is on Fire

Prior to exiting this world on January 16th, 2025, as if he’d stepped on to one of his own sets never to return, the American visionary auteur and iconic screenwriter David Lynch was evacuated from his compound deep in the Hollywood Hills amidst the Los Angeles wildfires. Due to the power of the bone-dry Santa Anas, occasionally called the “devil winds”, flowing down the inland Sierra and through the San Gabriel mountain passes and canyons to the sea, the only things1 to contain the flames were our tiny screens.

For a filmmaker for whom fire was a recurring motif, in company with flashing lights and electricity upsets signalling psychic ruptures and ominous thresholds through which his leads were about to be unearthed, it’s too eerie a fate to fully take in.

These winds, with their curious luminosity, set us on edge—raising serotonin, and occasioning static cling, and flyaways.

II. Forever Blue

Lynch loved Los Angeles for the light and sensation of freedom it gave him. Jasmine in bloom. The forever blue of the sky.

The coroner confirmed the cause of death was cardiac arrest due to COPD, and dehydration.

The stress of the evacuation had no doubt caused the emphysema he was diagnosed with back in 2020 due to smoking since the age of eight, to worsen.

Housebound for some time, he’d come to terms with no longer being able to direct in person, but insisted he’d never retire. Walking from one end of the kitchen to the other was, he said, like having a plastic bag over his head. This image of Lynch in an oxygen mask is uncomfortable enough, yet it comes replete with uncanny echoes of Frank in Blue Velvet (1992).

By Thursday night, the algorithm was alight with quotes, pics and clips of the director on set, smoking, playing cameos in his own films, being interviewed, being funny, being vocal on the transformative power of TM, and ideas being like fish on hooks.

For Lynch it was all about the idea, without which there would be no film, or painting, or album or experimental soundscape.

It was our task, as artists, he said, to then translate that idea into whatever form and medium we worked in. And it was his job to bring his loyal cast and crew members or “Lynch mob” (Hughes, 2009, pp. 209-210) along for the ride.

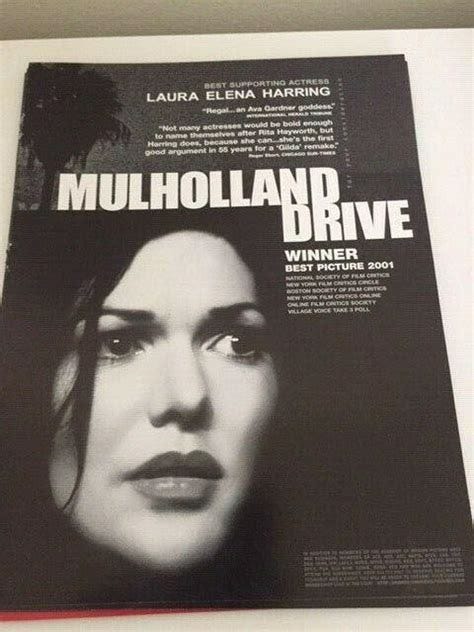

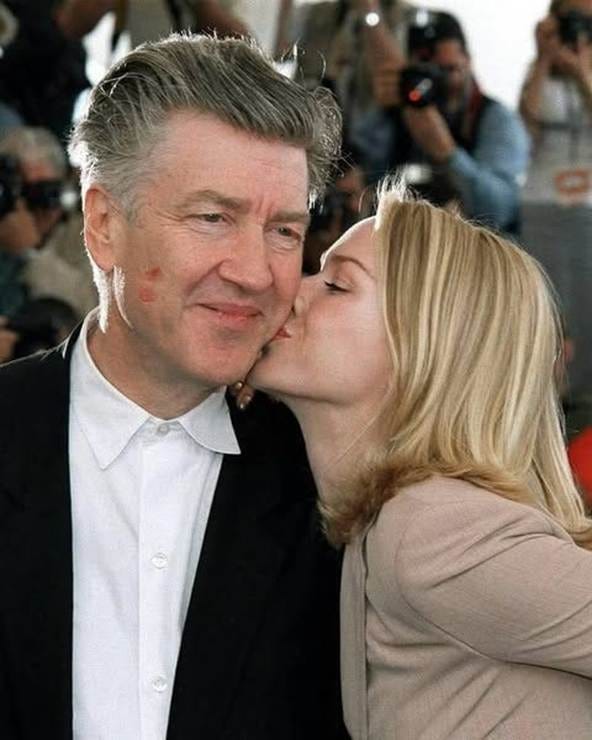

As Laura Elena Harring, who played the sultry brunette and amnesiac, Rita, in what is widely revered as Lynch’s magnum opus, Mulholland Drive (2001) (stylised Dr.) a mystery thriller which uncovers not only the duality of Hollywood but that of the female psyche, which Lynch repeatedly fractured, lauded: “All women feel love for David. He’s drop-dead gorgeous and when he smiles at you it’s like the sun is shining on you.” (Lynch and McKenna, 2018, p. 368).

Reels unspooled alongside intimate yet public expressions of loss from the actors he worked with, who clearly adored him.

A few months on and this collective tapping of hearts - because what else can we do? - has not stopped.

In place of one man’s eponym, Lynchian, in which the cryptic intertwining of light and dark coexists with chaotic love and the “ever-present possibility of things falling apart” (Lim, 2017) leading us to feel things we hadn’t felt before, is generative AI being stamped all over everything—leading us to feel nothing.

III. The Art Life

Coffee & cigarettes were, of course, part of his methodology. Lynch smoked on set, on screen, behind-the-scenes, when listening to rain, when painting, perhaps even when meditating, in interviews and in talk shows before it was outlawed. A prop for life, the art life, as he put it.

In the December 2024 issue of Sight and Sound magazine, he conceded:

Smoking was something that I absolutely loved but, in the end, it bit me. It was part of the art life for me: the tobacco and the smell of it and lighting things and smoking and going back and sitting back and having a smoke and looking at your work or thinking about things; nothing like it in this world is so beautiful. Meanwhile, it’s killing me. So, I had to quit it.

Then, there was that hair, like a prayer, as if it were going somewhere. But seriously, what man has hair like that into his thirties these days, let alone his late seventies?

IV. ‘A Woman in Trouble’

In response to critics such as Roger Ebert, who esteemed Lynch as a stylist but took umbrage with his transgressive direction and supposed “power play” with his then-partner Isabella Rossellini when directing Blue Velvet (which she rebutted), as well as with the matter of him not “wrapping stories up properly” so that “our hand closes on empty air”2 (Knight, 2025), he asked why people expect films to make sense when they accept life doesn’t.

Commenting on his final feature, for example, the 180-minute3 experimental opus and nightmare phantasmagoria INLAND EMPIRE (2006), which he shot himself on a consumer-grade hand-held Sony DSR-PD150 in standard definition and in which the cast had no real idea what they’d be doing on the day, he replied: It’s “about a woman in trouble, and it’s a mystery, and that’s all I want to say about it” (Blatter, 2006).

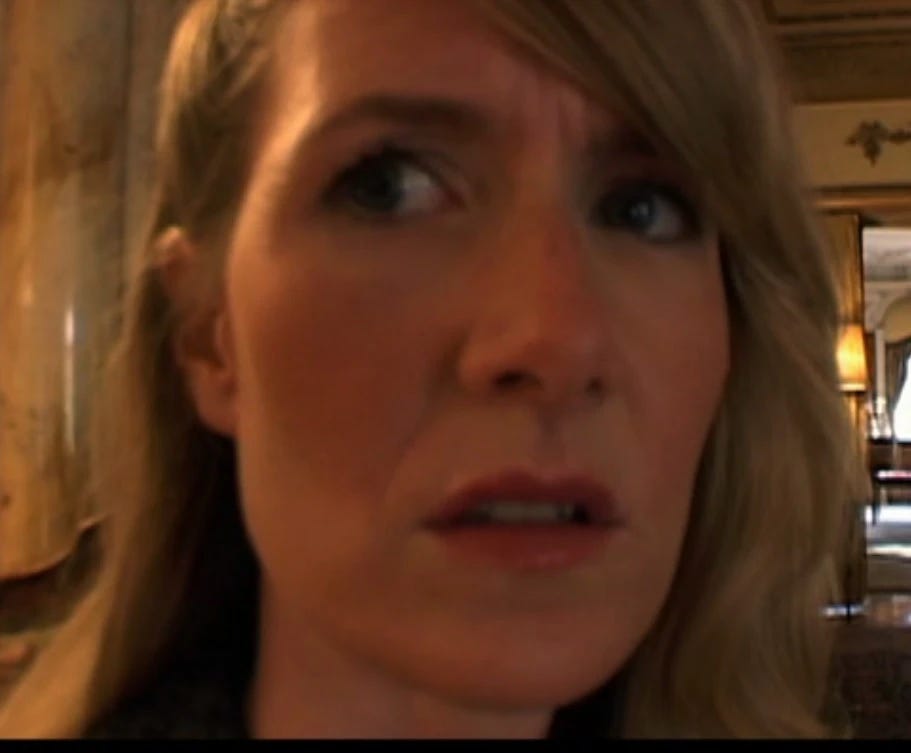

With the release of INLAND EMPIRE he announced he’d no longer be shooting on film. Video goes viral. It’s the medium of virtual rabbit-holes, YouTube grifters and gurus, amateur movies, surveillance, and porn. WBUR’s Sean Burns even described the movie as being “like it was photographed inside a toilet” (2022). Indeed, witnessing Laura Dern’s character Nikki Grace dissolve into the one she’s playing, Sue Blue, feels voyeuristic, like tuning in to a live feed.

Lynch portrays an associative mind—hyperlinked to infinity. He appears to be hunting down a kind of “direct and primitive contact with the world” in which art echoes phenomenology (Merleau-Ponty, 2012, vii), enacting a certain mood, a Heideggerian ‘Being-in-the-World’, or interconnectedness which chimes with his attentiveness to universal consciousness and cinematic truth.

In short, he’s thinking thorough video, as a painter thinks through paint, or a dancer, the body.

Bearing in mind the commercial pressures and physical impositions of film, which were increasingly at odds with his desire to “go dreamy” (Chotatatta, 2022), it’s an impenetrable violation of the genre. He goes to town with a preternatural style, all unnerving angles, grit, grain and noise (Lim, 2007), featuring inescapable close-ups of Dern’s face, verging on abstraction.

Despite the scope of theory interpreting Lynch’s uncanny through a psychoanalytic (Ruers and Marianski, 2022) or strictly Lacanian lens (Zizek, 2000; Asker, 2012) apropos the identity shifts and formation and deconstruction of fantasy in his films, it’s worth nothing that Lynch himself declined therapy.

He’d asked outright if the process would interfere with his creativity, to which the analyst couldn’t say it wouldn’t.

Similarly, in his advice to budding filmmakers he told them to always have the final cut, citing the thwarted epic space opera Dune (1984) (based on the book by Frank Herbert (1965)) as the thorn in his side.

In conversation with the American musician and poet, Patti Smith, who asked him if he had any inkling of the extent as to which Twin Peaks would sink into the collective unconscious, he replied with touching sincerity: “No, idea but the number one thing is to do what you believe in and do it to the best you can, and then you see how it goes in the world.”

I read he was cremated. All that brilliance gone to ashes, which also makes no sense.

V. Some Other Creature

I orientate the screenshot towards the sea, led by the star-like blooms of a dark blue-violet clematis up a driveway to the hotel.

Ring the bell.

Take the keys to room 3.

Undress.

Get under the shower.

Find a glass of prosecco on the landing.

Drink it.

Go down to the water.

Watch the tide coming in and think about how it won’t ever not, and how there’s truth in that.

Let the waves drum right through me.

Press record.

Catch the sky turn pink, then mauve, then indigo, then go hush but for the stars put there to remind us that none of this matters.

Not council tax reduction (CTR), broken kettle, or career.

And what are you going to do with the sea in your phone, anyway? Disappear? Re-emerge? Some other ocean? Some other creature?

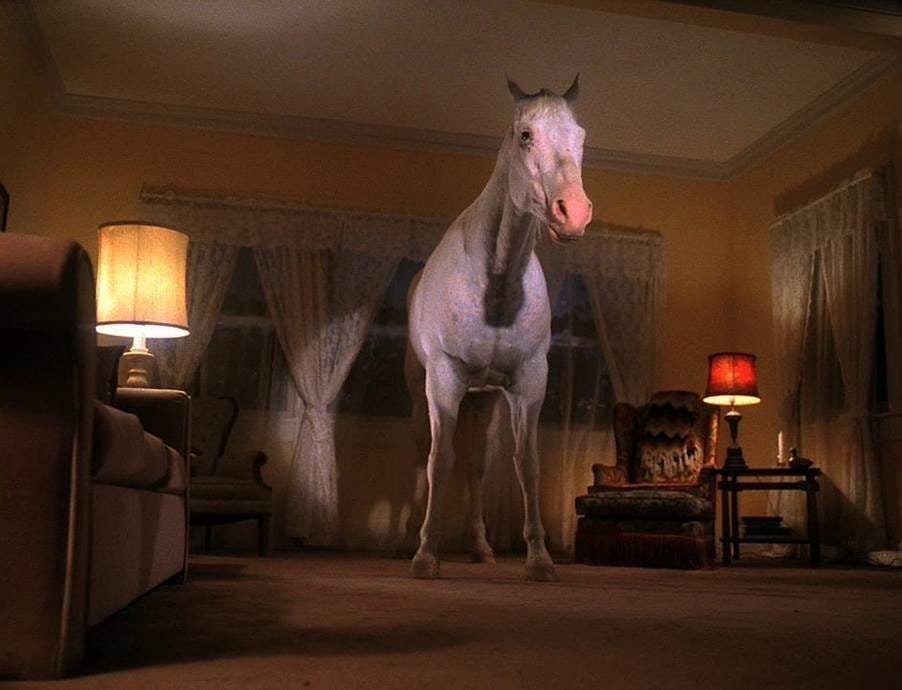

Gone was the man whose vision had single-handedly catapulted my 13-year-old imagination out of the Midlands town I was born in and through the TV into some dark American hinterland from which it never quite returned, where no one and nothing was what it seemed, thresholds lay in a lit up turn in a forest, or through a manicured red velvet curtain onto a zigzag floor, and a white horse stood in an empty living room.

We all know this feeling by now, of waking up and scrolling only to be hit by an iconic image of one of our favourite artists underscored by the present perfect tense: ‘X, the …. has died’, entombed in the parenthesis of a life (1946-2025).

What ensues is the collective outpouring of hearts, tear emojis, sincere comments, and clicks on the scores of companies, journalists, magazines or critics re-releasing clips of the deceased or giving away previously paywalled content for free.

VI. Paintings That Move

Lynch started out as a painter. He wanted to make paintings that moved. And in one of his ‘light bulb’ moments, he heard a gust of wind, and watched one of his paintings do just that.

Uninspired by art school, which he flunked, in part, due to his agoraphobia (all the more poignant considering his love of the spread out geography of L.A.), he enrolled first at the Boston Museum School and then at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he took to painting in a cube around the back of the building, seeding the art life as a way out of the alternative—“drudgery work”.

Being Generation X, my initiation into his world was the televised series of Twin Peaks (1990-1991) (co-produced with Mark Frost) which aired on BBC2 at 9 p.m. after the watershed.

I would sit cross-legged on the floor in front of the gas fire (the only place I’ve ever called ‘home’) magicked away from the orange square-ruled textbook which housed my Maths homework.

No notifications. No ads.

Just this dark, strange, forested place where electricity buzzed on empty streets to portend something bad was going to happen, uneasy characters sat in diners drinking endless coffee refills, and a woman carried a log and talked to it.

The best was, we’d have to wait a week until the next episode; whereas now we’ve got ‘view on demand’, and no need to wait for anything.

We’d talk about it the next day at school. Some of us stopped watching because it seemed to be going on forever and nothing made any sense.

When I was a kid, I asked my Dad how TVs worked because I just couldn’t get it. He was a television engineer, so I figured he should know. He told me that inside the TV were little men doing all the work for each show. But then he also told me he was superman.

As Lynch would have known and any painter comes to know, there’s an instant when you kill a painting.

One moment it’s free - and flowing - on the canvas, and the next, it’s fucked.

You went too far.

So, you scrape it back, madly, with a palette knife or a kitchen knife or whatever you’ve got going.

You dab it with linseed oil, or turps (depending on how organised you are), doing your best to retrieve it until concentric circles swell on the canvas, and it looks even worse.

The reality is you had it, and now it’s gone. And there’s no getting it back.

Lynch’s skill at manipulating light to invoke psychologically-charged and disorientating spaces in which the subconscious “leach[es]” into reality” (Heathcote, 2025) is not without reference to painting, of course. He was a master of chiaroscuro. As with Caravaggio, his use of light and dark not only evokes mood but both reveals, and conceals, information, or clues, if you like.

A vellum glow from a flickering lamp in a seedy hotel room initiates a sexual encounter; whereas a lone light bulb in an otherwise bare lounge sounds the isolation of the character about to walk into it.

Scrolling, on his passing, I couldn’t help but think how peeved he would have been at so many first timers coming to his work on the ’gram occupying crude violations of his lush compositions. He said films couldn’t be experienced that way. We might think we’re experiencing the film, but we’re not. He wanted us to be lured in, not subject to a siren song of apps, notifications, product placement4 or annual carousels of ‘memories’ designed to remind us of who we are. In his films, of course, his characters never really know who they are and are fated into trying to find out.

VII. Undertow

Lynch loved women. And it is women who are the undertow in his films. Despite accusations of misogyny and exploitation due to the graphic scenes of sex and violence in his work, often domestic in nature, actors have either denied or reinterpreted this. For example, paying homage, the American actress Chloe Sevigny praised him for writing complex roles for women that enabled them to transcend stereotypes, highlighting that this distinguished him from his male contemporaries.

And although he clearly had more than a penchant for (re-)casting disarmingly beautiful leads, and a roving affection and infidelities in his personal life, leaving three of his wives who all struggled to get over him (Lynch and McKenna, 2018), with Blue Velvet, he began to home in on ‘troubled women’—those who were both in danger and capable of danger.

Or, in other words, “[t]he woman inside the woman inside the woman”, as Laura Dern put it an interview with Kyle MacLachlan, with a tendency to remain out of reach—even to herself.

VIII. Audacity

Lynch’s 1997 neo-noir psychological thriller, Lost Highway, is located in a Möbius strip in which this unforgettable scene featuring David Bowie from the closing credits also occurs in the title sequence.

Lynch throws us into an atemporal loop and dream-logic populated with obscure symbols, unblinking characters, and doubling.

Many of the insane sonic textures and industrial dissonances produced by Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails were captured in situ whilst shooting on set into the vespertine hours; aggravating a paranoid tapestry of omniscient tech surveillance via video, telephones, intercoms, mirrors, white noise, and radio—prophetic then, but commonplace now. Breeding a phonic fusion of Rammstein, Marilyn Manson, Angelo Badalamenti, Lou Reed and David Bowie, with shadows of German Expressionism and the French New Wave, which is beyond hypnotic, Lynch gave Reznor nothing more to go on than an image of snakes in a box and the instruction to make it sound like a nightmare.

Living it, Badalamenti and Lynch even ventured to Prague to get first-hand recordings of the Prague Film Symphony Orchestra, which Lynch distorted by “plugging the recording cables into long thin strips of PVC pipe channelled through a large empty Chianti wine bottle” (Colman, 2006).

Backtracking to Eraserhead (1977), his debut surrealist black-and-white body horror and ultra-low-budget production is “pure ID” (Lynch and McKenna, 2018, p. 95), industrial grime, and alienation. Through its main character Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) Lynch mobilised his own paternal terrors at becoming a father for the first time to the extreme.

Critics have said Lynch is in all his films. And as someone who doesn’t buy into The Death of the Author (1967), I believe this to be so.

Another formative example that springs to mind is his father’s role as a research scientist working for the U.S. Forestry unit, the microcosm of which seeped into the sensational opening scene of Blue Velvet.

I’m fascinated how we come to be in our works and all the more, when not explicitly so. Yes, he played cameos in his own films, as did Hitchcock, but that’s besides the point.

Eraserhead was funded by the American Film Institute (AFT) where Lynch was studying at the time, having been awarded a fellowship in 1970 for his success with the four minute film and animation The Alphabet (1968), which he then followed up with The Grandmother (1970, 33 minutes).

Discussing process, he revealed: “I felt Eraserhead, I didn’t think it … I had these feelings, but I didn’t really know what it was about for me”. This refusal to impoverish his approach resonates with an interview with Nochimson (1997) where he admitted that “ninety percent of the time [on set] he didn’t know what he was doing”. In retrospect, he came to regard Eraserhead as his most “spiritual” film (Lynch and McKenna, 2018, p. 95), whilst appreciating that people wouldn’t necessarily get that.

Spelt had an extensive sound bank to hand, but none of it persuaded Lynch. So he went to Findhorn to rush winds through the score. These formative experiments in sound design spawned Lynch’s growing commitment to the “marrying” of sound and image - as he framed it - leading to him being regarded by many as the most important filmmaker of the current era.

He maintained that all this that we do, making songs, films, books, etc, is only surface stuff. Real change comes from within.

Hence, his initiation in 1973 to Transcendental Meditation (TM) and subsequent establishment of the David Lynch Foundation in his pursuit of “the ocean of pure consciousness” (Lynch, 2025), or bliss, happiness, or the unbounded - terms he used interchangeably.

Lynch scholars (Nochimson, 1997, 2013) have since theorised his layman’s interest in quantum mechanics/existentialism and the unified field as the “physics of David Lynch” (Nessun, n.d.), situating his work in relation to temporal manipulation and associated concepts such entanglement, superposition, and the Many Worlds theory. Whereas metaphysics fuels key transformations in his films, in which characters shape-shift, or appear to be in two places or time zones at once—thwarting a rational framework and reminding us of what might lie beyond constructed certainties.

IX. Lost Highway

Since his passing, I’ve been asked to recommend his films.

Although not an easy introduction, for there isn’t one (Kermode recommends The Elephant Man (1980) for the uninitiated), I’d begin with Lost Highway, as it operates with a dream-logic, and you’ll be in at the deep end.

It opens with the line: “Dick Laurent is dead”. (Lynch purportedly received a similar call on the phone when he was a kid.)

This comes through the door intercom of the apartment of the avant-garde jazz saxophonist Fred Madison (a moody and impotent Bill Pullman) in the grip of a psychogenic fugue and his dark-haired, emotionally distant, yet immaculate wife, Renee (Patricia Arquette).

In Lynch’s most disrupted chronology, what we’re actually witnessing is Fred’s admission of murder from the end of the film, coupled with the swirling of sirens by on duty police outside his house, put there to protect him, who are in fact, chasing him.

The couple then start to receive anonymous VHS tapes on the porch. Renee finds the first one on the stairs.

She hands it to Fred, who plays it. But all it shows is the outside of their house. She relaxes, and puts it down to a real estate agent.

The videos then escalate to reveal the couple sleeping.

X. “This Magic Moment”

In keeping with his unruly methods, the actor Balthazar Getty tells of how Lynch cast him as the teenage car mechanic Pete Dayton on the strength of a photo he’d seen of him in a magazine. Lynch called him in for a meeting, and “pretty much gave him the job then and there” (Lynch and McKenna, 2018, p. 336). This was genius as I can’t imagine any other actor holding that expression on first laying eyes on Alice Wakefield as she gets out of the Cadillac in slo-mo, which I’ll come on to shortly.

Getty also told of how Lynch got him to sit on his hands, so his face would do the talking.

Similarly, on casting Robert Blake as Mystery Man (in what is touted to be the most eerie scene in Lynch’s oeuvre), he did so after watching him on The Late Show. Swayed by his candour and lack of industry pretense, he bore him in mind.

Fred Madison stars getting headaches in his cell.

He then inexplicably morphs - or rather, bursts - into Pete Dayton, in who he’s manifest the inverse of his own failed masculinity.

With this psychic ‘split’, Lynch revamps his staple trope of identity as being fluid—fuelled by desires, traumas, and the subconscious.

As it goes, Pete already has a hypersexual girlfriend, and has no problem in attracting the attention of femme fatale, Alice Wakefield (also played by Patricia Arquette in a platinum blonde wig) who just happens to be the mistress of mobster, Mr. Eddy, who isn’t really Mr. Eddy, but Dick Laurent, a porn producer.

Pete doesn’t know what is happening to him. He just knows this all feels weird, like he already knows the blonde, which he does.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had the below clip on repeat as I’ve been writing this piece.

The way the guitar brews. The way he looks at her, and just keeps looking. There’s no end to it. And no beginning.5

XI. Room to Dream

In the 2018 hybrid biography Room to Dream, co-authored with the American journalist Kristine McKenna, we find Lynch in conversation with over 100 others from actors to agents to ex-wives to partners, to family.

It’s a novel experiment in form which usurps the pitfalls of traditional memoir. McKenna takes one chapter, then Lynch responds to what has been said about him in the next, and so on, forming an intimate biography in which he corrects them on what they said, and tells it as it ‘really happened’.

MC: David Lynch, you don't like doing interviews, do you?

DL: No I don't . 6 And when he did do them, he refused to be cornered into stretching his work out on the rack of the exegesis.

In this most watched clip with Mark Kermode, he displays perfect comic timing, exhibiting how he came to master the art of them (Harris, 2024).

Being notoriously difficult to pin down, interviewers with a more psychoanalytical bent, such as the ex-LIVE from the NYPL director, Paul Holdengräber, got nowhere with him, but laughs.

He was also the only person who could use the word beautiful as often as he did, and get away with it.

Lynch purchased the almost brutalist compound in Senalda Rd., Hollywood, which doubled as Madison’s house in Lost Highway (1997) to build his “sonic experiments” in a home studio; the first of which was the ambient/electronic album Lux Vivens: The Music of Hildegaard of Bingen (1990) (Lux Vivens, which translates as ‘living light’) co-produced with the British musician Jocelyn Mongomery.

The horizontal slats in the upstairs windows would assure that Fred Madison would only ever have a restricted view of the driveway from any vantage point. Such bleeding of art into life echoes how he and his first wife Peggy Reavey (m. 1967-74) painted their third floor black to transform it into a film set when they lived in Philadelphia in the 1960s (Lynch and McKenna, 2018, p. 72).

Lynch’s musical endeavours were eclectic and leave an unswerving legacy upon electronic, avant-garde, and ambient artists, as well as sound designers and in the broader cultural sphere.

He released two albums, Crazy Clown Time (2013) and The Big Dream (2011), which fused dream pop, blues, and electronica. He also christened the exclusive Parisian Club Silencio, hidden six flights below ground level in the 2nd Arrondissement, which was famously inspired by the Badalamenti-driven cabaret scene in Mulholland Drive. And went on to influence musicians as diverse as Moby, to Trent Reznor, to Kanye West.

With his endearing “Weather Reports”, which he posted daily on his YouTube channel David Lynch Theatre (short films, works, and surprises) during Covid-19, giving ritual to lockdown and some light relief for the legions of fans who tuned in, he often gave a shout out to whatever song sprung to mind. In the best of the internet in which it operates as a gift economy, this kind user has curated a playlist of songs Lynch referenced in his weather reports.

Post-INLAND EMPIRE, working primarily with sound, painting, and on more obscure projects, he also directed music videos with the likes of the Swedish singer-songwriter Lykke Li.

"I'm Waiting Here" is one such example.

I love the way nothing happens for the duration of the song, but the driving. Then, as the outro occurs, he rounds us into the back of a motel at dusk, and leaves us there.

Concurrently, he collaborated with the American singer and model known as Chrystabell, most recently on their 2024 album Cellophane Dreams (Chrystabell and Lynch, 2024). Yet, his proposed music video for Kanye West’s “Blood on the Leaves” never came to fruition, which Lynch felt bad about. He just couldn’t come up with the idea.

XII. Dark Continents

In Room to Dream (2018, p. 52), he cites his early preference for brunettes, “librarian types, you know, their outer appearance hiding smouldering heat inside” just like Audrey Horne (Sherilyn Fenn), from Twin Peaks, one imagines.

Having been married four times, he conceded, ironically, that it [marriage] “doesn’t fit into the art life” (Lynch and McKenna, 2018, p. 84).

He bore four children, one from each of his marriages and he was the one to walk away each time (Emily Stofle filed for divorce in 2023 after 14 years of marriage). He was also the one to end his five-year relationship with the actress and model, Isabella Rossellini, who starred with aplomb in his psychosexual thriller and seminal dissection of America’s ‘white picket fence’ Blue Velvet (1986) (Helen Mirren turned down the role thinking it too risqué).

Reflecting on their often long-distance affair, Rossellini figured she was wired for charismatic, influential men just like her own father, Roberto Rossellini and ex-husband, Martin Scorsese (1979-82). An aside, or an insight, perhaps, but Lynch complained about Rossellini’s cooking smells permeating all his notebooks and artworks—as if he wanted them to be pure of the real world.

His female muses all tend to what Freud terms the “dark continent” of female sexuality and its hidden epistemology. Unexplored psyche, soul, terrain, virgin forests, moist woods—ways in.

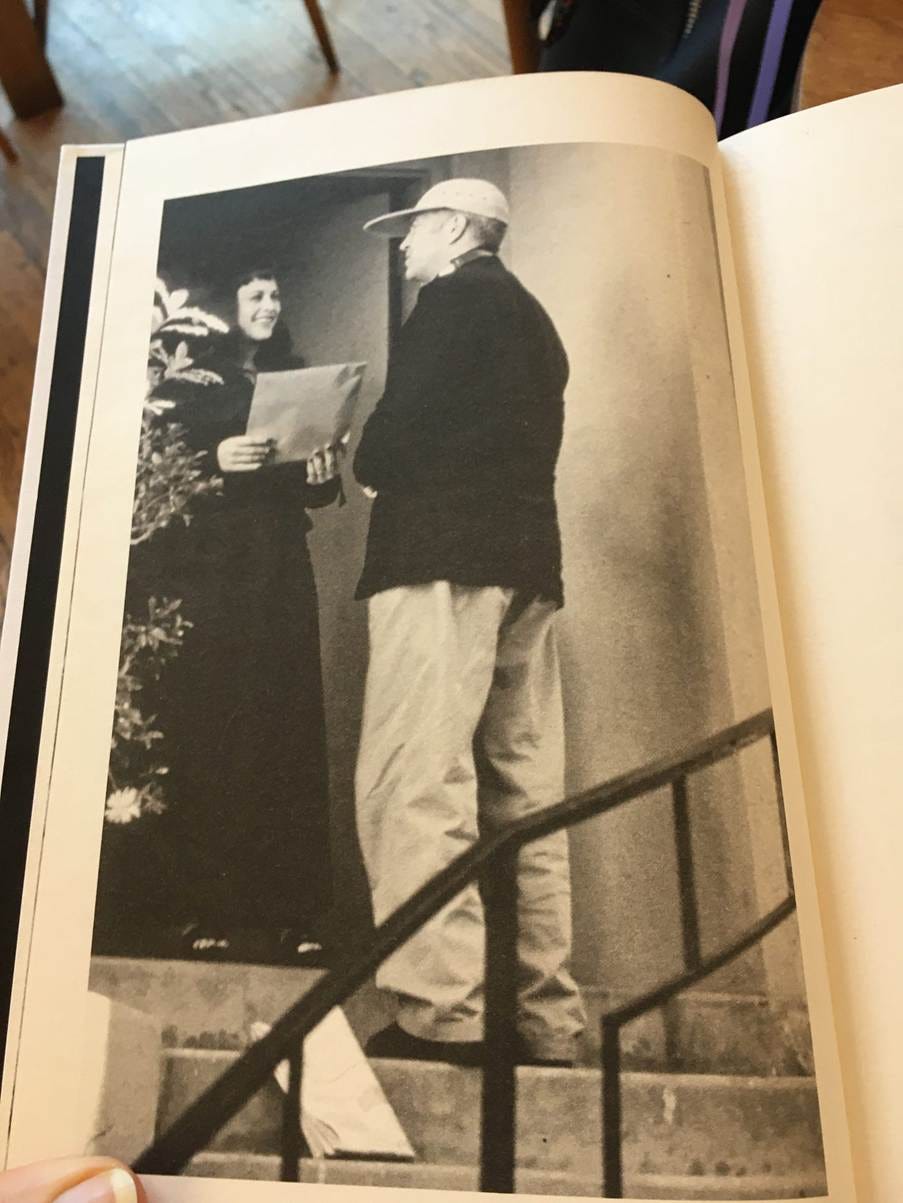

Lynch’s adoration for the women he tended to re-cast is clear in any photo of him caught on set with the likes of Laura Dern, Naomi Watts, Laura Elena Harring, Sheryl Lee or Isabella Rossellini, as in the one below which captures them falling in love on set.

He also had a tendency to pluck actors from nowhere, and change their destiny. Amidst the many celebrity testimonials which surfaced on social media following the news of his death, for example, several stood out to me.

Kyle MacLachlan who Lynch first cast as Agent Dale Cooper in Twin Peaks said that he owed his entire career, even his life, to Lynch, who had “invented him”, recently accepting the Laurel Award for Screenwriting Achievement on Lynch’s behalf in this touching speech. Whereas the British actress Naomi Watts had been struggling to get auditions in Hollywood for ten years before Lynch gave her a lifeline by casting her in her dual role as Betty/Diane in Mulholland Drive, which catapulted her to stardom.

Watt’s agent had put it to her bluntly that in her desperation for roles she was coming across as “too intense”, and “putting people off”. Lynch, however, bypassed this sea of insecurity.

On auditioning Watts, he forewent protocol, and instead got her to talk instead about her day, as if he genuinely wanted to hear about it.

One imagines him searching for that particular quality, or, as with Betty, naivety, which would translate on screen, despite the actress already pre-empting rejection. Her self-esteem was at an all-time low. “How did he even “see me” when I was so well hidden, and I’d even lost sight of myself?!” (Watts, 2025).

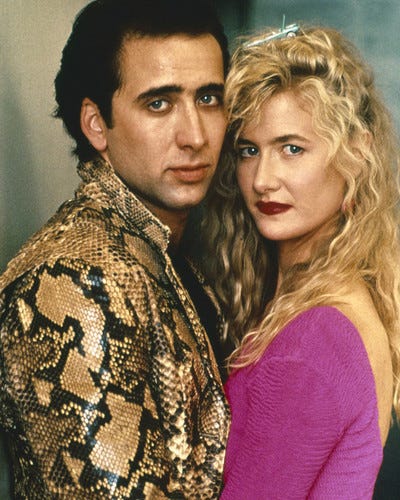

XIII. Wild at Heart

I’d then recommend the feverish road trip and comedy drama, Wild at Heart (1990). Nicolas Cage excels as the Romantic and wondrously dysfunctional Sailor Ripley who Laura Dern’s sexpot Lula Pace Fortune falls dangerously in love with.

Lynch relished working with Cage, for his spontaneity, abandon and bravery to take the character where ever it needed to go. Whereas Cage recalls it so: “When I was doing Wild at Heart, I was a very serious, young actor and I said, ‘David, is it okay if I have fun on this movie?’ He said, ‘Buddy not only is it okay, it’s necessary’” (Luxford, 2025).

I’m standing to his left. On set. He steps out to direct. I clock a hair net. But I can’t speak, the way we can’t speak in dreams.

His trousers hitch up, to reveal a metal leg.

Again, I can’t speak.

Now, I’m in a swimming pool.

There’s a machine on the coping blowing fresh raspberries into the water.

I bet they got it off Amazon.

XIV. “You Mark Me the Deepest”

Lynch had a real thing for the fifties, and the ‘purity’ of the decade, masking a darker side. And this aesthetic penetrates his films from pop music and culture, to fashion, to the names of his characters, to dialogue, to set design. With Wild at Heart , it was sex and Rock ‘n’ Roll.

The opening scenes are brutal, as was the original ending, which he was forced to revise. As a provocateur, Lynch would push it unless he really had to let go of an idea because it wasn’t the “right time”, as he came to reconcile it.

The screen tests here were a case in point where even members of the ‘David Lynch’ audience, let alone the ‘Disney’ ones, fled the auditorium. So he gave them the happy ending they wanted. And the film demands one.

Cage relays the story of the snakeskin jacket, which he’d picked up one time knowing he’d use it one time.

Once cast, and finding his feet in the role, he got Lynch to write it into the script, giving him the line, if not the mantra: “This is a snakeskin jacket! And for me it’s a symbol of my individuality and my belief in personal freedom.”

It remains Cage’s standout performance.

Besides, show me a guy who’d run across a stream of cars to get us back, girls? The likes of Sailor don’t exactly hang out on Hinge, sadly!

Sailor Ripley is every mum and dad’s worst nightmare, the violent anti-hero with a tender streak your daughter just can’t resist. And he and Lula spend the film fleeing from a crazed cast hired by Lula’s mum (her real life mother, Diane Ladd) to take him out.

“You mark me the deepest,” Lula tells him.

Wild at Heart won the coveted Palme d’Or at the Cannes International Film Festival in 1990, the only award Lynch really cared for. He was delighted that Federico Fellini, who had that year released The Voice of the Moon (1990) (La voce della luna), would also be in attendance. Yet, despite this milestone, critics reckoned he was parodying himself.

Speaking out on the sex scenes, Dern (Lynch and McKenna, 2018, p. 293) told of how she and Lynch sat down and watched the film again together during the making of INLAND EMPIRE, with neither of them having done so since its release:

When it ended we felt really moved. It was like looking through a scrapbook and all the memories came flooding back. I love the bed scenes the most. I love working with David when we’re in a car or a bed and there are isolated characters and everything else sort of stops in a way that only happens with David.

References

Akser, M. 2012. Memory, Identity and Desire: A Psychoanalytic Reading of David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. CINEJ Cinema Journal, 2(1), pp. 58–76. [Accessed 15 February 2025]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5195/cinej.2012.58

Blatter, H., 2006. David Lynch turns his eye to 'Inland Empire'. WFAA.com. [Accessed 15 February 2025]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20070928045413/http://www.wfaa.com/sharedcontent/dws/ent/stories/090406dnGLempire.64579170.html

Burns, S. 2022. Reconsidering David Lynch's 'arduously long' film 'Inland Empire'. Wbur. [Online]. 4 May. [Accessed 10 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.wbur.org/news/2022/05/04/inland-empire-david-lynch-commentary

Chotatatta. 2022. David Lynch lashes out at crew for not letting him go dreamy. [Accessed 20 January 2025]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-AHUEON7Fb8

Colman, F.J. 2006. Painting Film with Velvet Sounds: David Lynch’s Lost Highway. CTEQ Animations on Film. Issue 40. [Accessed 16 January 2025]. Available from: https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2006/cteq/lost-highway/

Han, B.C. 2022. Non-things. Upheaval in the life world. Translated by D. Steuer. London: Polity.

Harris. D. 2024. This hilarious clip of Mark Kermode interviewing David Lynch is one for the ages. The Poke. [Accessed 10 February 2025]. Available at: https://www.thepoke.com/2024/10/16/this-hilarious-clip-of-mark-kermode-interviewing-david-lynch-is-one-for-the-ages/

Heathcote, E. 2025. David Lynch’s interiors will haunt us forever. The Financial Times. [Online]. 30 January. [Accessed 2 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.ft.com/content/5b27a235-af19-4784-bd36-34ad1f8152c2

Hughes, D. 2001. The Complete Lynch. London: Virgin.

Lamodi, S. 2025. Decoding David Lynch’s ‘familiar yet strange’ cinematic language. The Harvard Gazette. [Online]. [Accessed 21 February 2025]. Available from: https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2025/02/decoding-david-lynchs-familiar-yet-strange-cinematic-language/

Knight, B. 2025. Roger Ebert hated David Lynch movies until ‘The Straight Story’. Movieweb. [Online]. Accessed 22 February 2025. Available from: https://www.movieweb.com/roger-ebert-hated-david-lynch-movies-until-straight-story/

Lim, D. 2007. David Lynch goes digital: Inland Empire on DVD. Slate. [Online]. [Accessed 23 February 2025]. Available from: https://www.slate.com/articles/arts/dvdextras/2007/08/david_lynch_goes_digital.html

Lim, D. 2017. David Lynch: The art life: Go with ideas. The Criterion Channel. [Accessed 10 February 2025]. Available at: https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/4976-david-lynch-the-art-life-go-with-ideas

Lim, D. 2007. David Lynch goes digital: Inland Empire on DVD. Slate. [Online]. [Accessed 23 February 2025]. Available from: https://www.slate.com/articles/arts/dvdextras/2007/08/david_lynch_goes_digital.html

Longhair, M. David Lynch interview. [Online]. [Accessed 9 March 2025]. Available at: https://longair.net/mark/random/david-lynch/

Lynch, D. 1996. Lost Highway. Audio clips. David Lynch’s personal website. [Accessed 16 February 2025]. Available from: http://www.lynchnet.com/lh/sound.html

Lynch, D. 2025. David Lynch on mediation. The New Statesmen. [Online]. 17 January. [Accessed 14 February 2025]. Available from: https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2025/01/heaven-place-earth

Lynch, D. and McKenna, K. 2018. Room to dream. Edinburgh: Canongate Books.

Luxford, V. 2025. Nicolas Cage pays tribute to David Lynch during awards speech. NME. Accessed 21 February 2025. Available from: https://www.nme.com/news/film/nicolas-cage-pays-tribute-to-david-lynch-during-saturn-awards-speech-3834203

Needham. J. 1988. The Devil Winds made me do it: Santa Anas are enough to make anyone’s hair stand on end. Los Angeles Times. [Accessed 18 February 2025]. Available at: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-03-12-li-942-story.htm

Nessun, A. n.d. Interview. The physics of David Lynch. Antonia Nessun’s Personal Website. [Online]. Accessed 2 March 2025. Available from: https://www.antonianessen.com/filter/Interview/Interview-The-Physics-of-David-Lynch

Nochimson, M.P. 1997. The passion of David Lynch: wild at heart in Hollywood. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Nochimson, M.P. 2013. David Lynch swerves: Uncertainty from Lost Highway to Inland Empire. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Ruers, J. and Marianski, S. Eds. 2022. Freud/Lynch. Behind the Curtain. London: Phoenix Publishing House.

Watts, N. 2025. Naomi Watts [Instagram]. [Accessed 16 January 2025]. Available from: https://instagram.com/p/DE54x8uvOXp/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link&igsh=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==

Žižek, S. 2000. The art of the ridiculous sublime: on David Lynch’s Lost Highway. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Discography

Chrystabell and David Lynch. 2024. Cellophane memories. NY: Sacred Bones. [Digital LP]. [Accessed 10 February 2025]. Available from:

David Lynch. 2007. The air is on fire. [CD]. US: Strange World Music.

David Lynch and Jocelyn Montgomery. 1990. Lux vivens: The music of Hildegard von Bingen. US: Mammoth Records. [Online]. Accessed 2 February 2025. Available at: https://www.discogs.com/release/975710-Hildegard-von-Bingen-Jocelyn-Montgomery-with-David-Lynch-Lux-Vivens-Living-Light

David Lynch: The art life. 2016. Rick Barnes, Olivia Neergaard-Holm, Jon Nguyen. dirs. [DVD]. New York, NY: Duck Diver Films.

Dune. 1984. David Lynch. dir. USA: Dino De Laurentiis Entertainment Group.

Eraserhead. 1977. [Film]. David Lynch. dir. USA: American Film Institute.

Inland empire. 2006. [Film]. David Lynch. dir. France: StudioCanal.

Lost highway. 1997. David Lynch. dir. France: Asymmetrical Productions.

Mulholland Drive. 2001. [Film]. David Lynch. dir. France: StudioCanal.

Twin peaks. 1990-91. David Lynch. dir. [Televised Series]. David Lynch. dir. USA: Lynch/Frost Productions.

Wild at heart. 1990. David Lynch. dir. USA: Polygram.

In Non-Things… Han continues his negative tract of the digital order, distinguishing between ‘things’ and ‘non-things’. Smartphones are in the latter camp. Whereas real objects and rituals are things which ground us, non-things are part of the ever-expanding digital ‘infosphere’. However, data is not knowledge, shedding constant dissatisfaction, restlessness and alienation.

Ebert’s criticism on narrative having to make sense is missing the point. Regardless, he went on to give Mulholland Drive (2001) a perfect score, claiming that Lynch takes “what was frustrating in some of his earlier films, and instead of backing away from it, […] charges right through”.

My last album Space Junk (2023) is 182 minutes. Recording alone without studio impositions, an engineer, cost, or time restrictions, I had free-reign to record and curate the album as I wished, giving it free reign. Working in the cheaper domain of video similarly enabled Lynch to ride with it.

One of my favourites.

This extract is from a Scene by Scene interview with Mark Cousins, transcribed by Mark Longhair.

Thanks that was a good read! Very revealing and beautifully written and illustrated. I love David Lynch movies.