‘Spontaneous song’ – that is songs composed freely in the moment of production without a pre-set duration – can be conceived of as soul music born from within. Such song matters as it cannot be predicted, re-written, re-recorded, generated by AI or ‘boxed in’, proposing an antidote to the persistent sameness of algorithmic culture.

Spontaneous song has its roots in The Bible1 (The Holy Bible: New international version, 1979) as a form of prophecy, and divine communion, through spirituals, gospel and blues. In congregational worship, it is practised as ‘call-and-response’ with the minister. It can also be ‘Googled’ as contemporary phenomenon.

When we make songs, there is the question of who we are singing to, and why. Song can be conceived of as devotionals, or offerings. The producer, Rick Rubin (2023)2 frames it so in The Creative Act. A Way of Being, a book which includes commentary upon the role of spontaneity in the creative process. Yet, the late Sinead O’Connor, being interviewed by the Irish talk show host, Tommy Tiernan on 1 February 2020, suggested that, despite the grander narratives we might associate with our songs, when singing, we are mostly talking to ourselves.3 Perhaps she is right.

Backtracking to the American Civil War (1861-65), slaves on the plantations regularly engaged in work songs or holler songs. Moreover, it was not uncommon for them to gather in illicit improvisation circles at nights in the woods around the plantations and make music. In this sense, their singing was a form of protest. In the case of field or holler songs, it was a way to punctuate time and relieve the burden of labour by giving it rhythm.

Singing was thus a way to transcend the body fashioning a discourse of freedom. Yet, contemporaneously, what of ‘freedom’ for the neoliberal or “achievement subject” when the term has become synonymous with “self-exploitation”4 (Han, 2015, 2017, 2020; Varoufakis, 2023).

As indie artists, we are now required to be ‘content providers’, marketers, and social media moguls who are never not on, promoting, performing and curating our lives for free. Corporations profit from us doing so, whilst simultaneously limiting who sees our ‘content’, and we are subject to fickle algorithms. We do not have a contract with social media, and the algorithm is just doing its job.5

A contemporary reclassification of spontaneous song is that of #speedsongs,’ #speedsongwriting, or ‘speed co-writes’. A basic Google, Instagram, YouTube, Pinterest or TikTok search shows us that the phenomenon is alive online. Examples are often hosted on channels run by members of Baptist congregations, mostly in the US, or by recording artists who are religious and who write their own songs.

What ‘speed songs’ offer is a short-cut to writing a song. As ever, the emphasis is on saving time (in a time where none of us have any time) and cutting the emotional labour, and creative process, out of the equation. This is symptomatic of the late- capitalist ideological illusion that we can have this, or that, without the negative consequences of doing so.

For example, the US singer-songwriter, Graham English, is not untypical in offering a free ‘cheat sheet’ as a downloadable PDF in exchange for an email address. Similarly, channels such as those run by YouTuber, Diane Laine, with clickbait titles, such as “Write Songs Quick! How to Write a Song in One Hour or Less!” (Dylan Laine, 2017)6 are not hard to land upon. There is clearly a demand for exponential songwriting, then.

On the back of this trend, The Knoydart Retreat (2023), (a songwriting retreat based in the remote North of Scotland), are currently advertising a “speed co-writing retreat” with professional songwriters via their Instagram feed and social media. It is worth questioning who exactly these types of courses are for (considering their cost) and what accounts for this trend. Why do people want to write songs quickly? And how does one do so with a pen and paper approach? What do these retreats offer? Then there is generative AI, which I will come to in later posts, which will iron all the labour out of the process. This would seem tied to how ideology functions in terms of desire and to ‘the commodification of everything’ (Wark, 2019; Hall, 2023)7 including the creative process.

If one unravels how ideology functions in terms of desire (in that one might simultaneously partake in an activity whilst being alleviated of our guilt in doing so), as Žižek8 explains: “A desire is never simply a desire for a certain thing. It’s always also a desire for desire itself” (quoted in Diogenes the Cynic, 2018, 2:16-2:26).

In this sense, ideology lives out in our daily habits of consumption. In the track, “Forever Chemicals”9 on Space Junk, for example, I sing about being in Starbucks and reading the signs at the counter which assure us that by buying our coffee there we can “…help save the children of Guatemala / And it’s included for free in the price.”

One of the artist, Jenny Holzer’s, famous truisms reads (Jozelit et al., 1998):10

Speed songs, co-writes and courses would also seem to offer convenient solutions to privileges such as ‘writer’s block’. There would seem to be more than a hint of the ‘libidinal economy’11 (Lyotard, 1993; Samman and Gammon, 2023) implicit in such promises of expediency. Yet, as the philosopher and mystic, Simone Weil, suggests in Gravity and Grace (1947)12, attention is akin to prayer, a phrase which has taken on a meme-like quality, all the more prescient in our dopamine culture where privacy is the last bastion.

It might seem ironic to mention this, considering I am engaged with self-disclosure and personal and political testimony by writing online, in the midst of curated online identities and automated ‘fakery’.

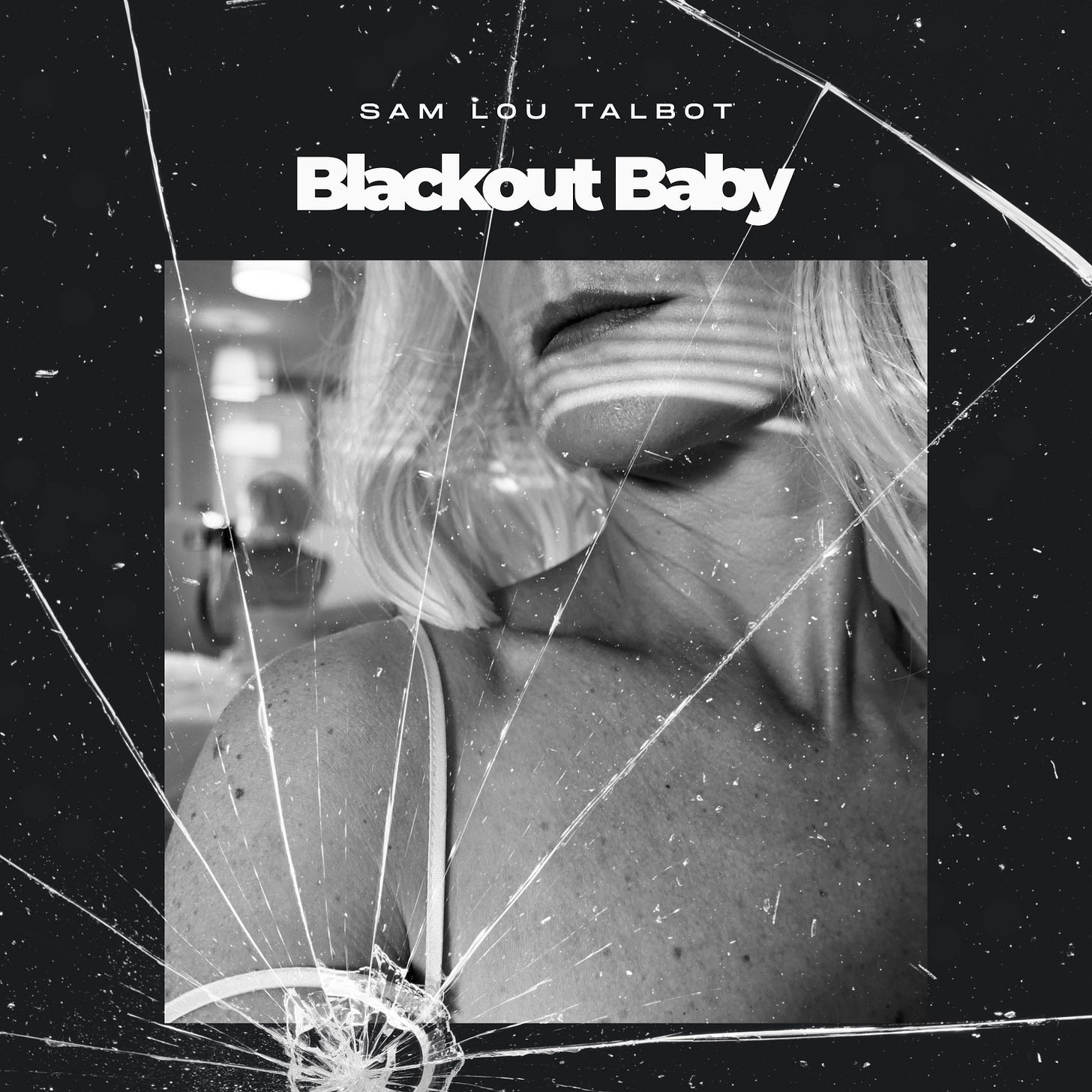

To finish on a lighter note, my new EP - Blackout Baby13 - is out today. This is the sweet four-track sister production to Space Junk, as the songs were recorded in the same sessions yet they seemed to demand their own identity. This is delicate and raw material tenderly mastered by Nick Lewis of Old Cottage Audio, who I recommend.

Holy Bible: New international version. 1979. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Rubin, R. 2023. The creative act: a way of being. Edinburgh: Canongate Books.

Pille K, 2020. Sinéad O'Connor aka Shuhada’ Sadaqat on The Tommy Tiernan Show 2020/02/01. [Online]. [Accessed 15 May 2021]. Available from: https://youtube.com/watch?v=0G9YPvsG_c4

Also see, O’Connor, S. 2021. Rememberings. London: Penguin.

Han, B. 2015. The Burnout Society. CA: Stanford University Press.

Han, B. 2017. Psychopolitics. Neoliberalism and new technologies of power. Translated by E. Butler. London: Verso.

Varoufakis, Y. 2023. Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism. London: Vintage.

Sujon, Z. 2021. The Social Media Age. SAGE Publications. [Accessed: 15 October 2022]. Available from: https://www.perlego.com/book/3013488/the-social-media-age-pdf

Dylan Laine. 2017. How to write a song in one hour or less! (Songwriting 101). [Online]. [Accessed 17 December 2023]. Available from: https://youtube.com/watch?v=44FEsk3FMGA

Hall, D. 2023. ‘Commodification of everything’ arguments in the social sciences: Variants, specification, evaluation, critique. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. [Online]. 55(3), pp.544-561. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221128305

Wark M. 2019. Capital is dead. London: Verso.

Diogenes the Cynic. 2018. Žižek explains the appeal of Coke. [Online]. [Accessed 15 October 2023]. Available from: htps://youtube.com/watch?v=SJOhtDmyy-4

Talbot, S.L. 2023a. Forever chemicals. Sam Lou Talbot. Space junk. [Online]. Glasgow: Sam Lou Talbot. [Accessed 12 October 2024]. Available from: https://samloutalbot.bandcamp.com/track/forever-chemicals

Joselit, D., Simon, J., Salecl, R. and Holzer, J. 1998. Jenny Holzer. London: Phaidon Press.

Lyotard, J. F. 1993. The libidinal economy. London: The Athlone Press.

Samman, A. and Gammon E. eds. 2023. Clickbait capitalism: Economies of desire in the twenty-first century. Manchester: Manchester Scholarship Online. [Accessed 15 October 2024]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526168177.00010

Weil, S. 1947. Gravity and grace. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Sam Lou Talbot. 2023d. Blackout baby. [Online]. Glasgow: Sam Lou Talbot. [Accessed 20 December 2023]. Available from: https://samloutalbot.bandcamp.com/album/blackout-baby