Audio article

“The thing about an idea”, says David Lynch, in an interview montage, “is that it wasn’t there, and then it’s there” (Cosmavoid, 2021, 06:32).1

In late November, 1974, the German visionary auteur, Werner Herzog, set out from Munich to Paris on foot. He was headed to the deathbed of his friend and mentor, the film critic, Lottie H. Eisner convinced that in doing so, he could save her life. As it went, she did live, for some time and Herzog’s quixotic diary of his three-week, five hundred mile pilgrimage was documented in feverish and hallucinatory present tense in the book Of Walking In Ice (Vom Gehen im Eis) first published in 19782. He also wanted to be on his own for a while, chronicling it all back to us, from the lucid edge—mirroring any one of his films.

I was speaking not so long back with the American critic and curator, Paul Holdengräber, who has interviewed Herzog on several occasions3. He assured me that Herzog did not think of himself as a Romantic, as I had suggested. Yet, Herzog’s undertaking resonates with that of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who, in 1777, rode out on horseback from Weimar, travelling a hundred miles (160.93 km) north to the forest of the Harz region, seeking a sign, or a portent, following his sister’s death earlier in the year. He did this to confront himself, and his limits. Pilgrimages take many forms then.

In Agnès Varda’s feminist masterpiece Vagabond (1985)4, the protagonist, Mona, a sixteen-year-old unfiltered and unaffected Sandrine Bonnaire is found frozen dead in a ditch in the opening scene, her body not yet decomposed. Varda then cleverly pieces Mona back together in the rear-view mirror via a litany of characters and non-actors (some desirable, and some less so) that Mona encountered in her final weeks and days prior to quitting her job as a secretary in Paris, changing her name and going on the road, determined not to be defined by the system fated for her. Mona flaunted the mantra: “Je m’en fous – je bouge”, I don’t care, I move on. Yet, this was not a despairing or forlorn take on life but rather a “a Whitmanesque celebration of everything human” (Flitterman-Lewis, 2000).5

Varda, fondly known as the “Grandmother of the French New Wave” was experimenting with cinéma verité at the time. Her faux documentary style (in which she would also come in and out of the frame) leant her films their idiosyncratic and yet ostensibly political vibe. Her debut, La Pointe Courte (1955), is so affecting because it is the result of a woman with ideas trying her hand at filmmaking without any formal training whatsoever. She did not know the rules to break them, fact. In these works, life bleeds into art.

Vagabond was inspired by the story of a woman found frozen on a field which Varda had read about in the papers. Life bleeds into art (as it does on these pages). She then went to talk to, and informally interview, a string of homeless people by listening to their stories and paying attention to them. In short, she made them feel heard.

This care for the marginal and displaced is evocative of John Berger and Jean Mohr’s (1975)6 A Seventh Man and Berger’s classic trilogy Pig Earth (1979)7, the latter of which is his spirited trilogy on escaping the North London literary bourgeoisie (he had been writing for The New Statesman). He then decamped in permanent exile to the French countryside, where he would remain, to live amongst and with peasants, charting the eclipse of their life and rituals through his trademark, painterly attention to a sensual examination of the seasons, written in short and surrealistic verse, illuminating our common humanity and what we have come to lose.

Vagabond translates in French as Sans Toit Ni Loi, “with neither shelter nor law”. In Mona is contained an impulsive, even feral, quality which compels people towards her, without them quite understanding why.

Within the women she comes across, she inspires envy, comingling with fascination (her very essence, or élan vital makes them question their own, or lack of), or that which has been ironed out of them by life.

In one scene, an academic, Mme Landier (played by Macha Méril), picks Mona up and they drive around for a bit. Revolted by Mona’s bad smell (but also compelled by her), class distinctions come to the fore. Mona’s more immediate, sensual, responses to the physical geography they wind through contrast with her own. There is also an epiphanic scene in the film in which Mme Landier gets electrocuted messing about with a poorly fitted lamp. Critics fielded something of the divine into it, suggesting this could have been Mona waking Mme Landier up from the stupor of her unsatisfactory marriage. As Mona is uncovered through the stories told about her, though, we are reminded that none of us are seen or will come to be seen in the same way by anyone we know.

In another scene, Mona eats fish; it glistens on her lips. Her eroticism and untranslatability unnerve others. Her fate would appear to be sealed as she wanders about the Languedoc Roussillon wine country in winter at the mercy of the contingency and kindness (or otherwise) of strangers (she is raped).

She takes payment for sex, sleeps on roadside verges, or where ever she can, loving her boyfriend but maybe not enough and believing that she can have out of capital, and her lot, when she clearly cannot.

Aside from the nomadic element, or vagabonding, what unites both Herzog and Mona is their unflinching individualism, or lack of restraint and heroism.

Herzog’s mental state descends as he lives off milk and tangerines, his feet swollen and sore, breaking into shelters like a vagrant and occupying the liminal thresholds of a major filmmaker gone rogue in the death frost of a German winter.

Mona, deep down, must have been, scared. It takes risk and courage to get up and go, not knowing what will happen.

In September, 2023, I carried an amp on my back across Europe. A friend of mine asked why, prompting this post. But the problem with extrapolations post facto is that we are, at our best, an unreliable narrator. I have ideas as to why, of course, which I’ll outline below.

Guy Debord and The Situationists reclaimed cities and public space as being that which we can wander about in, have contingent encounters, or go on dérives. Their revolutionary method of urban wandering in groups designed to sabotage the boredom and ennui of the Spectacle8, which would be a nice idea today in the attention economy if we were not all glued to screens of every size. Social media can be viewed as an extension of the Spectacle (Nunn, 2019).9

As with improvisation, per se, unstructured, chance, and contingent encounters can encourage a type of concrete sociality which resists the atomisation of the neoliberal subject under advanced capitalism in which our emotions are exploited by corporations for profit. It could be said that we are currently experiencing what the cultural theorist and film scholar, Catherine Liu, in an interview with the underground theorist and internet culture researcher, Joshua Citarella (2024, 01:27:47)10 describes as “a new form of psychic enclosure” of the commons.

The Surrealists, had, of course, preceded Debord in epitomising the revolutionary imagination of touch via a chance meeting upon the street, in which two strangers lock eyes. This is symbolised in André Breton’s cornerstone of Surrealism and exemplar on desire, the novel and dream-like book, Nadja (1999)11 (originally published in 1928).

Nadja (1999) opens with the question “Who am I?” (p.11) and is shot through with disarming, and often cited, lines, such as the final sentence: “Beauty will be COMPULSIVE, or it will not be all” (p.160).

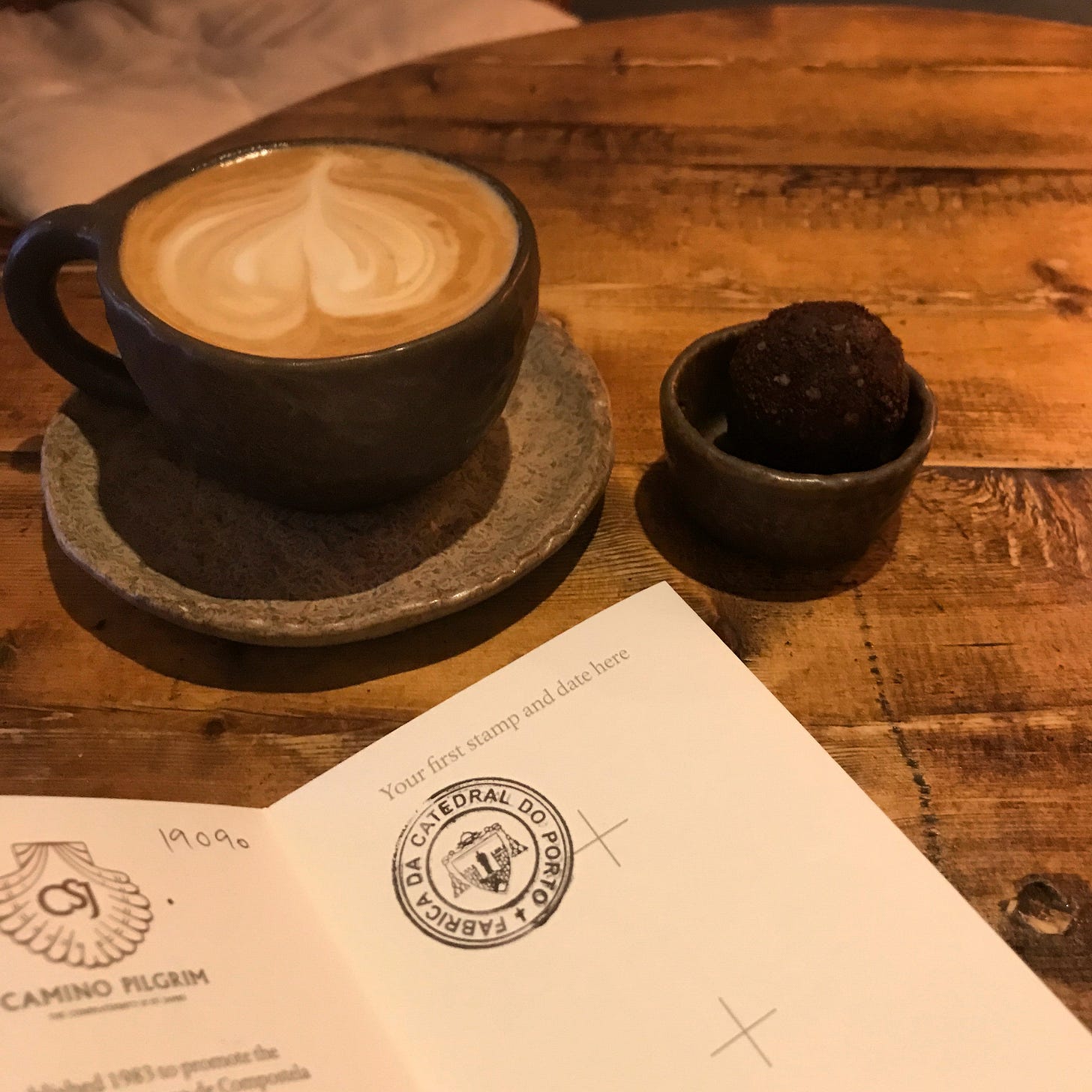

I was sat in a cafe in Porto, with an album scheduled for release in two days. Anticipating the pending non-event, I decided to undo it. If listeners weren’t going to come to my music, I’d take it to them, which meant doing something IRL. As Attali reminds us, in Noise: The Political Economy of Music (1985) music is a subversive act. Moreover, on rejecting established methods, he remarks, “[o]f the only worthwhile researchers: undisciplined ones” (p.133).12

At Edinburgh airport, my rucksack weighed in at just over 13 kilos. I gradually reduced this to around 11 kilos as I discarded non-essentials along the route.

Leaving Porto meant keeping the river on my left, and following a series of yellow arrows. The river would then turn into The Atlantic Ocean.

For 12-14 days, I would walk 280 km, averaging 22-29 km a day, carrying an amp on my back, with no time for rest days. The act of simply getting up and going every morning, heading out at 6:30 a.m. in the dark, waiting for the light to break open the sky, was wonderfully simple and straightforward. Each day brought with it a certain amount of mileage, and a route. Besides, after breaking my collarbone in November, last year and doing a gig forty eight hours later, in which the footage reveals I was even standing on a chair, in dialogue with the drummer, at one point in the night—we can do anything if we really want to.

I found the above sign in Ribeira, Porto on one of the main thoroughfares. Just alongside was an Italian opera singer flaunting her reverb outside H&M. A little further along were three teenagers, singing, dancing and clapping for the cameras.

I then clocked a photographer with an antiquated pinhole camera from which you could have your photo taken for ten euros. Across the bridge, over the River Douro there stood a bear playing an electric guitar in 30 degrees heat.

The next morning I followed the sound of music to the cathedral, got my passport stamped, and then found myself wandering the narrow alleyways of Ribeira. There was washing hanging out, brightly coloured plant pots, and cats watching.

I happened upon this public toilet with a gratuity box and no attendant. Inside, was washing up liquid in lieu of hand wash. I’m not sure why I am drawn to photographing such banal images like this, but here.

In contrast, back in Glasgow, we’ve had a cold spell of late. I’ve been hiding out under the quilt, watching films. I re-watched Jonathan Glazier’s hypnotic and luminous Under the Skin (2013)13 last night. This is a film of uncanny presence over plot, in which a series of events are loosely connected. It unfolds more like a dream than a coherent narrative, orbiting the disarming beauty and incongruity of Scarlett Johansson driving a white van down Argyle Street with hidden cameras, luring these incidentals back to her place and no sooner unlocking the door, than walking them under a desirous sea of black oil as they disrobe, their dicks rock hard and ready to implode to that killer soundtrack.

Then, there’s the sheer otherworldliness and primeval force of the Scottish landscape, with panning shots made uneasy by the faint engine of a threatening motorcycle getting closer. It really is hypnotic. As the film unravels, her character slowly gains empathy, lingering upon her reflection in the mirror: Is this me?—symbolising the sense of estrangement and deep-seated need for connection common to all of Michel Faber’s protagonists.

I stopped for a morning coffee next to this pharmacists, drawn in by the neon sign. It was 29 degrees centigrade, and only half past nine. The barista was having a panic attack at there being three of us in the queue. She then apologised. I asked her if she was okay and her friend translated for me. They wished me a bom caminho.

Paulo, a photographer friend of mine based in Lisbon said I should come to Portugal for the light. I initially trained as a painter and still tend to think of ‘composition’ as a painter would, in terms of what is falling in or out of the frame. (This tendency is clearly marked in how I composed the Liner Notes lyric booklet for Space Junk).

I exit Lidl, on a roundabout, to concrete into glory, captured by the light falling upon the foliage outside these apartment blocks. And lone cats sat in windows.

I caught this singular rose in full bloom. Its gorgeous rouge offset against the discoloured walls. The camera can’t really capture it, of course.

YouTube recommends a podcast with Nick Cave in conversation with the host, Krista Tippett, who approaches her interviews with spiritual overtones.14 She asks Cave a specific question on ‘improvisation’. He goes on to explain that he and Warren (Ellis) will just go into the studio, mess about for a bit, get something to eat and not really speak, then go back into the studio. He describes the process of improvising between them as one of love (Tippett, 2023).

I had a clear stretch of the ocean before me and a bright blue sky. All I knew when embarking on the trip was that I wanted to release the album via Bluetooth over The Atlantic, and why not? It was an image I had in mind that I then lived out. Such ideas have an erotic charge.

I took the tripod and positioned it on a suitable rock, checking the frame. I then recorded the impromptu performances dotted along the Portuguese coast and in the Spanish mountains on my other phone. Pilgrims and passers-by halted their progress to watch and record me on their phones, as they had done in Venice a year prior on the “Space Junk Broadcast Tour”. The video below uses the same methods of documentation to capture me wandering around Venice with my amp, and performing in public space, disrupting the flow of tourism in a city which is effectively a stage set.

On the Camino, my actions prompted conversation later in the alburgues, and en route, and expanded my ‘reach, leading to new ‘followers’. It also led to the exchange of stories and dialogues which prompted me to retell the ideas behind the album, and to narrativise the PhD process.

Just north of the surf town of Esponsende the coast is wild and untamed and the beaches resembled the West Coast of the US, or so it felt. I found random spots on the beach to unpack the amp and set up the tripod to record myself doing a series of interpretive dances to the opening instrumental track, “Glory Skin”15 and to the Native American drum and chant inspired “Dream Catcher”.16

At points along the way were boards like this, littered with signatures and dates, a form of testimony. I didn’t have a marker on me so did my best to promote the album with a ball point pen. It was the absurdity of this promotional ‘stunt’ and my carrying the amp that aroused curiosity.

A Czech woman called Katerina who I kept seeing on the route and I found this gas station in Viladesuso. Inside, brazen, there was this cat. I have nothing else to say other than it appeared to be posing amidst the barbie regalia, candy and confectionary—savouring the limelight.

Just along from the gas station, we found this man blowing bubbles outside his caravan. The bubbles here were tinged pink with the sunset.

Sure I needed a rest stop. By day four, I was having visions of ceremoniously dumping the amp in a verge so I booked myself in for a rest stop but the next morning, I got up, and out and passed the accommodation by. Walking like this gets compulsive, a rhythm sets in.

Heading onwards towards the Spanish border, Katerina and I had lunch with two Irish men, Dan and Charlie, and a group of other pilgrims. We had the wind in our faces all the way. Most of the route was exposed to the ocean wind which we were walking into for 29 km. The others stopped for the night in Viana do Castelo, yet we three carried on to Carreço. The last 2 km went on forever. Charlie took my mind off it by streaming Merry Clayton’s infamous audition on “Gimme Shelter”.

Clayton was pregnant at the time and when Mick asked her to do it again, she was determined to show them, and that she did. There’s no other recording like it, if you haven’t heard it. It is sheer electric. I get goosebumps every time I listen to it. It’s as if she put all of her pain and everything she’d ever felt into that second take. You can listen to the isolated vocal here.17

As it went, the bar in the photo above wasn’t open. Charlie and the other walkers were booked in separate accommodations so we all met for dinner that night. It was a strange town dominated by an illuminated church on the top of a hill, which we tried to capture on our phones.

There was one restaurant up the hill with set menus you had to chose from and the locals were having a family birthday party. It was the 29th September. The album had gone out into the ether that morning, so we drank to that.

The next day, and halfway along the route, at a small town (intriguingly called Arcade) I took a room with full board and spent the afternoon sunbathing and swimming in the pool.

I bought oranges.

That particular day had been a winding and uphill battle through forested regions. In addition to the muscle pain, I had blood blisters and strange heat rashes on my ankles spreading to my calves. I also had water blisters from mosquito bites the size of coins on my thighs. A New Zealand man said to me: “Whatever you’re doing, I think you should stop”. He was surprised to see me reach the alburgues before him each day.

I photographed these purple flowers which were everywhere. They are called Morning Glory, or so I was told.

We had crossed over on the fully-booked morning boat from Caminha to Padron and were now in Spain.

The cake you see below is typical of that which is free all over Spain when you buy a coffee. The one below cost one euro 20 cents and it’s hard to imagine this custom in the UK.

I was in the old city of Vigo, booked in at a municipal alburgue for which the pilgrim’s credential is compulsory. These places are run by the government to cater specifically for pilgrims. On checking in, one gets given a protective cover for both the mattress and pillow but no duvet. There was also a kitchen but it was ‘against regulations’ to use it, and there were no utensils to do so.

The night brought in an Olympic snorer on the bunk opposite. After tutting, sighing, and rolling over this way and that, for an hour or so, plotting my next move, I was delighted to have an accomplice in the form of a German girl in the adjacent bunk who got up with a start, announcing: “I’m going to prod him”.

I jumped down from my bunk with glee because I too was going to prod him, but no amount of prodding worked. In the end, she, her boyfriend and I all went out to sleep on the open terrace. I still remember it, the slow light and occasional city sounds, the faint wind.

Others slept in the corridor.

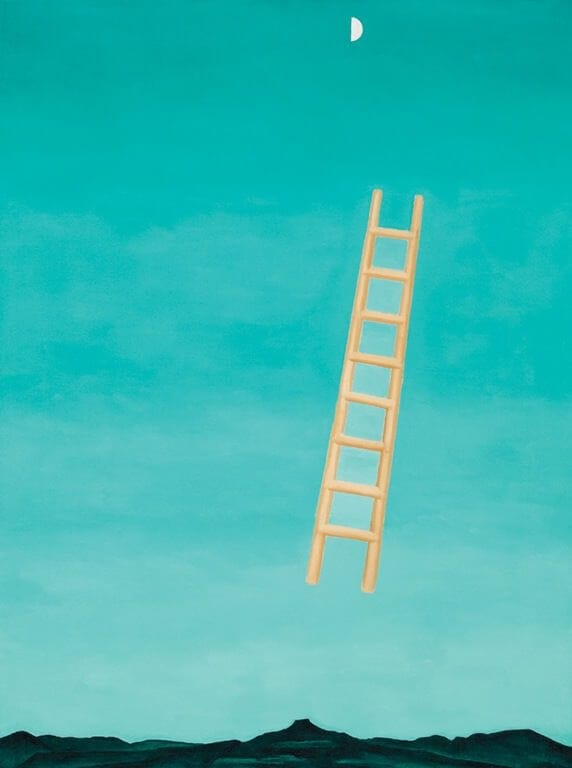

We were under the stars. I lay like a sardine on the thin protective sheet, with my leather jacket pinned around me. I felt like Georgia O’Keeffe sleeping on the roof at Ghost Ranch, in Santa Fe, which she regularly did, preferring to be connected to the elements. Around this time, she painted Ladder to the Moon (1958), an impossible painting, and possibly her only truly Surrealist work.18

Porto – Santiago in 12 days Carrying an Amp on My Back, 28 September -10 October, 2023. Self, backpack, Blackstar amp.

Cosmavoid. 2020. David Lynch being a madman for a relentless 8 minutes and 30 seconds. [Online]. [Accessed 15 November 2022]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TqZpi8zAqe0

Herzog, W. 2014. Of walking in ice. London: Vintage.

Onassis Encounters. 2019. Werner Herzog in conversation with Paul Holdengräber. [Online]. [Accessed 15 November 2019]. Available from: https://www.onassis.org/whats-on/werner-herzog

Vagabond. 2011. [Film]. Agnès Varda. dir. London: Artificial Eye.

Flitterman-Lewis, S. 2000. Vagabond. 15 May. The Criterion Collection. [Online]. [Accessed 20 March 2022]. Available from: https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/78-vagabond

Berger, J., Mohr, J. and Blomberg, S. 1975. A seventh man: a book of images and words about the experience of migrant workers in Europe. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Berger, J. 1979. Pig earth. London: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative.

Debord, G. 1977. The society of the spectacle. 2nd ed. London: Practical Paradise Publications.

Nunn, E. 2019. Social media as an extension of Guy Debord's The society of the spectacle (1967). JAWS: Journal of Arts Writing by Students. [Online]. 5(1), pp. 79-91. [Accessed 28 October 2023]. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1386/jaws.5.1.79_1

Joshua Citarella. 2024. Catherine Liu: Trauma, virtue and liberal elites. Doomscroll. [Online]. [Accessed 22 September 2024]. Available from: https:youtube.com/watch?v=Ia6m3pIIS2k

Breton, A. 1999, Nadja. Translated by R. Howard. London: Penguin.

Attali, J. 1985. Noise. The political economy of music. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Under the skin. 2014. [Film]. Jonathan Glazier. dir. London: StudioCanal.

Tippett, K. 2023. Nick Cave. Loss, yearning, transcendence. On Being with Krista Tippett. [Podcast]. [Accessed 27 November 2023]. Available from: https://onbeing.org/programs/nick-cave-loss-yearning-transcendence/

Sam Lou Talbot. 2023h. Glory skin. [Online]. [Accessed 12 October 2023]. Available from: https://youtu.be/EqGsT2aLY7U

Sam Lou Talbot. 2023g. Dream catcher. [Online]. [Accessed 13 October 2023]. Available from: https://youtube.com/watch?v=00GqSUMYROo

Roundtable with Drew Dempsey. 2023. “Gimme Shelter” isolated vocal by Merry Clayton. [Online]. [Accessed 28 November 2023]. Available from: https://youtube.com/watch?v=fdACTl2myMA&t=6s

O’Keeffe, G. 1958. Ladder to the moon. [Oil on canvas]. At: Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.