And if the body does not do fully as much as the soul?

And if the body were not the soul, what is the soul?

- Walt Whitman, “I Sing the Body Electric” (1867)1

… live, live even more intensely.

- Julio Cortázar, Autonauts of the Cosmoroute (2008, p.367)2

I want to discuss the soul in a materialist way. What the body can do, that is the soul, as Spinoza said.

- Franco “Bifo” Berardi, The Soul at Work. From Alienation to Autonomy (2009, p.21) 3

I

Structures of desire

Last week, I introduced Spanish AI model influencer, Aitana, who, whatever fate may wield it is highly unlikely to be a “bullshit job” (Graeber, 2018).4

This week, we have ELVIS, resurrected in the form of the Ensuring Likeness Voice and Image Security (ELVIS) Act put in force last Thursday by the Governor of Tennessee, Bill Lee, to protect the intellectual copyright of artists and Nashville’s lucrative industry from unauthorized use by artificial intelligence.

Both take me back to ChatGPT having a stab at Nick Cave, an event which precipitated the Australian singer-songwriter and Bad Seed to respond in kind to a question from a reader who wrote in to The Red Hand Files to ask him what he thought of songs being written in the style of Nick Cave, with: “…the apocalypse is well on its way” (Cave, 2023; cf. Scarlett, 2024).5

Moreover, country singer and American idol host, Luke Bryan, who has been vocal in his support of ELVIS, says he’s been getting songs sent to him on his phone that sounded like him and that even he couldn’t tell the difference.

All of which brings me to Suno, which purports to be a “new AI music experience” to “help you break the barriers between you and the song you dream of making” (by taking all the labour out of it, seemingly). “No instrument needed, just imagination. From your mind to music” (Suno AI, 2024).6

On perusing Suno AI’s website, one finds a rotation of prompts. You can “make a song about anything”, “make a song about the moon”, “make a song that feels how you feel” or even “make a song for lunch”. All good so far, then. There are also “trending options”. Or you could opt for the Suno Valentine’s Day Experience and be in with the chance to win a bouquet.

On clicking the link, I land on a powdery blue 💙 on an otherwise black screen. This makes me sad.

There is too much space around the 💙 and nothing’s happening. I guess it could be a glitch at my end, or a download speed hitch. But my tristesse is soon abated as the 💙 bursts open with a call-to-action to get started.

What is the name of your Valentine?

I type in “Ben”.

Where did you and ‘Ben’ meet?

“Asda”.

But the next question appears with such haste that ‘Ben’ and I could have met anywhere, and Suno wouldn’t have cared.

What makes Ben special?

Easy peasy. “He can pick me up.”

Suno seems happy with that, but then wants my email, so I exit the site. No song for ‘Ben’, then, but I’ll live. And so will he.

I’ve written previously on the role of speed and consumption in the structuring of desire, the coordinates of which are fantasy. Seduced by short-cuts which offer this without that, ‘convenience’ tends to do our decision making for us. This can manifest in our enjoying products without their malignant properties, i.e. coke zero; decaffeinated coffee, sugar-free cakes, sex without sex; frappucinos without the guilt, as the signs by the counter in Starbucks convince us that our loyalty is helping to save the children of Guatemala and what is more, it’s included in the price for free.

Track 32 on Space Junk alludes to such ideological reasoning in the lyrics “Forever Chemicals” (Talbot, 2023a)7. The problem with PR or “libidinal engineering” as Fisher terms it, is that: “[l]iterally nobody is convinced by PR, you’d have to be an imbecile to believe it… When we hear that Upper Crust is passionate about sandwiches, we know they’re not, we know nobody is passionate about sandwiches, right… We don’t believe it but it’s still capable of making us doubt what we know” (Cci collective, 2016, 00:15:45-00:16:47).8 The sandwiches are convenient though.

On the subject of convenience, Tim Wu, professor of Law at Colombia University, contributor to the New Yorker, and author of The Attention Merchants: The Epic Scramble to Get Inside Our Heads (2016)9, coined the phrase “the tyranny of tiny things” in his often cited New Yorker essay “The Tyranny of Convenience”.

Wu maintains that ‘convenience’ is the most played down and miscalculated of forces, doing our thinking for us, and curbing other options, which may well be more enriching. Convenience also rejects process. In this time-saving utopia, anyone can do anything, until they can’t. I touched upon this previously here.

Devotionals

Devotionals are daily exercises, meditations, liturgical tasks, songs, a reading plan, essay, maybe even a re-stack. Yet the word is burdened by asceticism and religious overtones, self-sacrifice, abnegation, even masochism (as with the mystics). Such practices may lead to God; but what if God is already here?

There?

A small brown bird lands on the balcony. Non-descript, with no distinguishing features they lock eyes for ten seconds or so, then it flies off. In that ten seconds or so she is rooted to the kitchen floor, bare foot, and body electric, knowing she can't hold onto it, whatever it is.

In The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property (1983)10, the American essayist and poet Lewis Hyde redirects that classic text on gift exchange and reciprocity, The Gift: Forms and Functions of Exchange in Archaic Societies (Essai sur le don: forme et raison de l'échange dans les sociétés archaïque), written in 1924 by the French author and anthropologist, Marcel Mauss, to the lives of artists, with latter chapters on Whitman and Pound, respectively, (who remained abjectly poor and subject to monopoly capitalism without patronage). Mauss concludes that gift economies operate in accordance with three obligations: 1) giving; 2) accepting, and 3) reciprocating. In gesturing towards an economy of the creative spirit, Hyde’s overriding concern is “the gift we long for” which “… irresistibly moves us” (Hyde, 1983, xvii).

Hyde illuminates upon the word’s etymology, in that: “[t]he root of the English word “mystery” is a Greek word, muein, which means to close the mouth” (Hyde, 1983, p.280) (my emphasis)—pursuing his line of flight, in that gifts are mysteries, drawing upon anecdotes by Neruda, and others. Yet mystery depends upon the capacity to be enchanted; and we are living in deeply disenchanted times.

III

The primacy of things

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus contemplated the ontology of things and concluded that everything flowed: πάντα ῥεῖ (panta rhei), and that the only constant was flux. But his perception ran counter to the other pre-Socratic philosophers, including that of Plato, who, after Parmenides, (the philosopher of changeless being), deduced that the natural condition of objects was rest. Moreover, as the psychologist, William James, points out in his classic text, The principles of psychology (1890),11 people aged thirty and above rarely change, but rather tend to be solidified. Apropos physical transformations tied to masquerade in my own work, I have harnessed coloured wigs, costumes, projections and masks via the shoring up of a personal signature aesthetic.

Transformation is also problematic as a term, because it implies a total change of one substance to another, as in alchemy. Yet, consciousness raising depends upon it. In terms of research activities, the word is also often cited, research should be transformative, (at the same time as it should also be pre-figured, metricised, or regulated depending upon the field). Playing this game demands a certain trickery. The contemporary neoliberal university has been captured by market imperatives which tend to delimit experimentation, curtailing new modes of thought and feeling.

Ironically, transformation as a concept implying betterment, is often implicit in annual performance reviews and objectives. We can always do, and be more—the neoliberal fantasy. This culture of self-optimisation extends online. Instagram, for example, features numerous influencers, and creators, who reinvent themselves as life coaches, or ‘light workers’, often in their mid-twenties, and their business model necessitates that we are out of touch with ourselves, or that we do not know who we are, but should we buy a masterclass, or sign up for a transformative 1:1, we might (see my lockdown poem “Zoom to God” (2020).12

When it comes to change though, as the psychologist, William James, first identified back in 1890, people after the age of thirty rarely do. We know this of partners, and of ourselves. We may desire to change, recognise we need to, and try to do something about it. Yet we are predominantly defined by our past and discombobulated by our possible futures, operating within an ‘achievement society’ (Han, 2015)13 which falsely leads us to believe that we ‘can’ (Han, 2017)14 do anything— until we can’t.

In the UK, class permeates every bedrock, and yet to bring it up in conversation is risky proposition (which could even put you out of work). But class never goes away it just gets squeezed into other forms. Besides, there are more trending propositions: IP and a carousel of equality, inclusivity and diversity workshops being drawn up by the professional managerial classes. More to the point, a quick look at the staff profiles, and it becomes clear there is not much diversity in sight. However, as Ahmed, contends, perhaps “the most inventive academic work comes from those who occupy precarious positions,” as opposed to those more ingrained within the institution, or, exercising what she terms “institutional polishing” (Binyam, 2022).15

Moreover, the term ‘lived experience’, used in qualitative phenomenological research, has been appropriated by other disciplines. It may appear empowering, but it can also, conversely, shut down debate and counter-arguments when applied to one’s life. For a neat rebuttal upon the subject, I turn to the late Michael Sugrue (RIP), an American historian and professor of philosophy (1957-2024) whose incomparable lecture series has been uploaded to YouTube by his daughter Genevieve.

In 1992, Tom Rollins, of The Teaching Company, was recording a lecture series to be televised called Great Minds of the Western Intellectual Tradition. Yet the speaker got stage fright, and so Rollins persuaded Sugrue and his colleague and life long friend, Darren Staloff (see the all too brief Mike and Darren Unplugged), to lead the lectures. No PowerPoint slides here, just an immense passion and knowledge of the Western canon delivered with astonishing pace, charisma, and rationale. Sugrue’s lecture on “Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations: The Stoic Ideal” remains one of his most viewed. Sugrue hadn’t been well, though, for many years, and very sadly succumbed to metastatic cancer in January of 2024. When my friend WhatsApp-ed me to say Sugrue had died, I actually cried. One moment someone’s there; the next, they’re not.

It was more than that, though. The last time I’d seen him, he was on a live stream, asking where everyone was, and unable to understand why people who’d registered hadn’t shown up. He was still getting to grips with the tech., and calling out to his daughter, Genevieve, (who uploaded all his lectures to his channel, and was on hand in the other room). He’d been recording his lectures from home, talking straight to the camera, from his side room, and, for a time, sat on a plastic garden chair. Yet, the upload schedule became more sporadic. Testimonies flooded in to the comments section from all backgrounds; those without any formal education, the curious, the bored, the dispossessed, and those with criminal backgrounds, who said Sugrue had turned their life around. This is the internet at its best. I appreciated his dry and laconic wit, precisely because it wasn’t sarcasm. And when they got onto the subject of ‘lived experience’, he sallied, drinking horn in hand: “What then is ‘unlived’ or ‘non-lived experience’?”

IV

Space Junk

Space Junk is defunct, man-made debris hurtling principally in Earth orbit. It was also the title of my third album: the 34 track, five-piece, three-hour cosmic magnum opus (2023). I had intended to put this thing on vinyl but it was an ever unruly composition, which underwent three incarnations. Excess seemed the point though. As the feminist musicologist Susan McClary (1991)16 points out: ‘excess’ rejects hegemonic control to destabilise hegemonic power structures.

I’ve ordered Herzog’s new memoir,17 and a have a book on his “ecstatic truth” teetering on the edge of the table. Space Junk, in its excess, embodies a stubborn propulsion, echoing that we face in Herzog, or his protagonists, whose vision compels them beyond their reach (Prager, 2007).18

Intentions of transferring the album to a physical format began to seem redundant, as issues arose. These included the cost of quotes on a six vinyl cut which were extortionate. In addition, due to the high-dynamic range on several tracks, caused the cutter to advise a test press instead, suggesting that they would translate as surface noise on the vinyl, and be best suited to digital formats. I had the mastering engineer print the DDPs for the five pieces, which were spread over five discs, as I had curated the album. Sonically, and in terms of its lyrical narrative, I could not sequence the tracks easily onto the limitations of a 33rpm vinyl disc. The songs were running over, I was running over.

When it came to the release, I considered ‘drip-feeding’ singles, or releasing one a month, to build audience. But there was no audience! So, I decided to ‘drop it’, or release it in one go, like a purist. And it felt good. What became important was the release, and the ritual of the release, the meaning-making behind it, which lends it value.

Ironically, the more I worked on the album, and the bigger it got, the less I cared how it would be received. The album was released into the ether on 29 September 2023 whilst I was sleeping in a bunk-bed in a mixed dorm in a surf lodge in Esposende, Portugal. As David Grubbs contends in his introduction to his book on John Cage, Records Ruin the Landscape (2014) records represent an entanglement with the world.19

Regarding harnessing spontaneity when producing the album, I was concurrently learning how to use Logic, having opted to do the mixing myself, rather than outsource it. This executive decision may have come to have been the most crucial one in the process, as it resulted in me having full control over my sound world, in which the process of mixing was one of listening, over instruction.

It was anything but convenient, though. I virtually lived in monitoring headphones, traversing, the city, mixing and bouncing in cafes. I even had to have an MRI scan as I developed a buzzing in one ear. I was also experimenting with cocooning single-takes in textured, sonic landscapes, via freesound.org, a sound library to which users upload their sounds voluntarily, with various creative commons licenses.

In terms of gift exchange, and as part of the virtual commons, such democratic and utilitarian software subverts the problem of hierarchy which has always prevailed in gift economies which are an “erotic commerce, joining self and other” (Hyde, 1983, p.163). Freesound.org seems to me to be utterly democratic and generous, people uploading their sounds for others to appreciate or use.

I opened Space Junk with an instrumental track, “Glory Skin”20), which was the only position for this track. This was a risk as in terms of audience, as it being free of lyrics, and more atmospheric/experimental, it dose not ‘sit’ with the singer-songwriter genre and could have alienated some listeners.

Embellished with a primal Cornish sea scape, creating texture around the interior sound of my own mouth clucks and extended vocal techniques recorded spontaneously through real-time composition (listen to “Glory Skin”), I open with the interior of the mouth, venturing outwards. Besides, in the curation of this album as a sonic journey, there was no where else for this track to go.

The title for the album came from a WhatsApp family thread on my brother signing up to go into space via email, to which my Dad posed the question: “What about all that space junk up there?”

I knew immediately that that was to be it, and went into the studio the next day. This draws attention to the immediacy of an idea. As the visionary American filmmaker, David Lynch puts it (2017):

Desiring an idea is like putting a bait on a hook and lowering the bait into the water… (0:18-0.22). The thing is to be true to the idea. (1:22-1.26) …ideas that could take you out of drudgery work. (2:06-2:10)21

In this post, as an extension of my song making practice, there is also the sense of getting lost in the material to emerge through it. We make music as we make life.

Mad filaments, ungovernable shoots play out of it, the response likewise ungovernable,

Hair, bosom, hips, bend of legs, negligent falling hands all diffused, mine too diffused, …

- Whitman, (1867, lines 52-58)

On completing the album, and orbiting works, including its 54-page digital liner notes, the previous year’s broadcast tour in Venice (2022), I walked roughly 300 kms on the Camino Portugués coastal route from Porto to Santiago de Compostela in October, 2023 - via a boat trip on the Variante Espiritual - averaging 25 km per day and carrying a portable Blackstar amp (2023).

My rucksack weighed in at 13 KG at Edinburgh airport, but this lightened as I went. This ‘stunt’ doubled as both an unconventional album launch and a piece of episodic endurance/durational performance art. I had imagined The Atlantic on my left. I had visualised this, and now I was doing it, making it happen. I would use Bluetooth to release the album across The Atlantic Ocean. Why not?

I planned to forego GPS on the route, instead following the yellow arrows. I walked out of Porto.

I am helium raven and this movie is mine.

- Patti Smith, “Birdland”, Horses (Patti Smith, 1975)

V

Exposure

You can’t call it that”, said a friend.

“Why?” I replied.

“Sam. Throwing 34 tracks out there and calling it ‘junk’ seems like a self-fulfilling prophecy. Besides, there are more commercial prospects,” he said. “What about “Halo”?”

Yes, I had a song called “Halo”, but so did Beyoncé.

Regarding putting out the 34 tracks all at once: “You have no label”, another friend DM’d. “You can do what you like”.

Conjuring album art for a title such as space junk was no easy task. The only space I had to photograph in was domestic, a studio flat. Yet I worked on transforming this space. I sellotaped the Kodak Lumi 150 portable projector I’d used on the Venice tour to the top of the DSLR, and got to work screen-mirroring from my camera reel, which contained a trail of stars and moons. Conflicting light sources became problematic, though. I ended up with around 1800 photographs. In the image below, I conjured a partial eclipse, an orb, and, with the injection of sun, by a Spanish graphic designer, this image morphed into the album art.

I frequently exposed the hardware too, troubling the footage and blurring the boundaries between artifice and process.

In “The Land of Nod” (Track 2)22 there are occasions of a crescent moon wandering around the room, doubling in the mirror, turning into two moons, crossing. I enjoyed this sensation, illusion.

Editing this video was an extensive and time-consuming process with fifteen versions having been exported. It was then exported as a vertical video for online consumption. It had been shot in portrait mode on an iPhone, resulting in unpleasant sidebars. The edit contains rapid cuts, and is mostly focused on body parts, the accumulation of which lend it a fragmented visual identity. Towards the end of the video I used rapid cut and paste editing to incorporate a short clip of me hitching my night dress up my thigh, holding a rose. This repetitive cut mimics sexuality; in sync with desire running through the lyrics.

The above screen shots show fragments of my body, a hitched skirt, bubble gum pink lips in negative, the lace on my nightdress, in which various identities or personas get played out in the video via the transversal of colour schemes. On reflection, when editing, some of these personas came to the fore over others, as if in competition. It felt, on editing, like they were characters. This couldn’t have been pre-empted and only emerged through messy, organic methods. I had also straightened my hair, lending me a demure, physical demeanour, more so than the exhibitionist ‘look at me’ blue wig worn on perusing Venice, and in the music video “Blue Valentine”; or subsequently, the platinum blonde wig I used in the visuals for the final work produced on the PhD, the four-track Blackout Baby (the one cut vinyl which remains unopened).

In the photo below, I’m looking at you looking at me in the mirror: a triadic gaze. Or, I’m looking at me in the viewfinder. Or, you’re looking at me looking at you looking at me in the mirror. The order of looking is not set, we are plastic, mutable, existing in non-linear temporalities.

As reflexive visual research methods, both photography and video afford “defamiliarisation” (see Shklovsky, 1917, on “Art as Device”)23. This functions as a distancing method within which to present objects, ideas and concepts in new ways, which Shklovsky and the Russian formalists argued was the point of art. Such self-conscious and scopophilic tendencies when working with the body in performance art resonate with that of the American pioneer of 1960s-70s performance and video art, Joan Jonas (Morgan and Jonas, 2006).24

I have similarly engaged in reflexive methods of documentation and framing using mirrors, masquerade, and props in the music videos and artwork - recording, and replaying myself, both visually and aurally, and transforming or injecting wildness into domestic spaces in the process, such as with the use of moon and stars and screen mirroring in “The Land of Nod” music video.

Conjuring transformative sets loaded with myth, ritual and personal narrative, Joan Jonas (influenced by Borges) has continued to deploy mirrors as her ruling prop. As transitional objects - and our first encounter with the libidinal - mirrors have been used to interrogate the entanglements of the body and the recorded image.

Correspondingly, and in terms of the erotic, the French conceptual and performance artist, Sophie Calle, known for her intimate explorations of personal relationships, risk taking, and chance encounters, is known for incorporating bedrooms and hotel rooms into her carnal signature aesthetic, as in The Hotel, Room 47 (1981)25.

Sophie Calle’s seminal Suite Vénitienne (1979)26 is an interdisciplinary and hybrid exploration of desire and transience, based upon her stalking a man she refers to as “Henri B”, around Venice. The text influenced the “Space Junk Broadcast Tour” (2022) in which I also roamed the city but with an amp, making a noise, by using my phone and Bluetooth to broadcast the album-in-progress, disrupting the flow of capitalism and tourism as I went.

I sat with the amp by the Grand Canal and projected my voice over the water, singing to passing gondolas packed with tourists, which remains one of the most epiphanic moments of my life, in that everything felt in place. They all waved back, along with the gondoliers, and it was joyous. I also danced and performed outside churches and in public squares, using two phones, one to document myself with, and projected my documented performances onto exterior buildings and intimate spaces, such as the hotel bedroom, playing with scale and outside/inside, public/private. These public experiments were precursors to the subsequent Space Junk Album Launch in 2023.

VI

How’s your stats?

It has gone eleven, I’m sat watching the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore collapse, on repeat. The sound is on mute. Or the video has no sound. Six people are reportedly missing. The bridge sort of curls, and then folds, in an instant. I press replay, like a tick.

Han reasons in The Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present (2016)27 that the smartphone embodies restlessness and an over-reliance upon contingency. He goes as far as to suggest that through our dependence on it we have morphed into “phonosapiens” (2024). Han can get away without a smartphone though, I imagine him walking across his local park to his university, in Berlin, anonymous, as for me, I can’t even work my job without the Microsoft Authenticator app.

Watching tragedy (re)play out, other headlines pop up: DUP leader resigns after sex offence charges and “My one-bed flat’s service charge’s now 16K a year”.

Apple reminds me that last week’s screen time was 9 hours plus per day. Another video of the bridge pops up on my feed.

I wait five seconds to skip the ads, then remind myself, again, to get that ad blocker installed, and then it flicks to the Baltimore fire chief detailing the timeline of the rescue.

There were multiple people on the bridge, he says, and therefore presumed multiple vehicles in the water.

I boil the kettle.

On the table is a collection of books including Han’s new polemic The Crisis of Narration (2024) in which he’s rallying against “storyselling” over “storytelling” in his signature condensed, almost aphoristic, prose.

I open the fridge. Half an avocado sits on the shelf.

Our narratives have become units of information. However, “[i]nformation does not permit any lingering” (Han, 2024, p.19). And this is how our stories are sold to us now, he contends. They are not stories in the traditional sense of the word.

The sun is low, setting later after the Equinox. A couple are washing up in the apartment block opposite.

Another resident, who occupies an unrestricted riverside view, has blue white light on that is all too harsh. He mostly watches his 60-inch flat screen TV. Sometimes, there’s a dog in the room.

Han laments the communal fire in place of the digital screen—and our sense of continuity with it. This is why I come back around to sexuality, meatspace. Flesh and bones and sweat and moans.

In a recent spontaneous audio post I rally ‘against content’ partly because I am done with hearing the word but also because I had the impish idea to do something else with it, to run wild with it at gone eleven until the word lost all meaning (see ‘semantic satiation’, a term coined by Leon James in 1962).28

Inspired by Sontag’s 1966 collection of essays, Against Interpretation, I began toying with the syllable stress of the parts of speech, in a stream-of-consciousness voice memo.

CONtent (n.) vs conTENT (adj.) CONtent (n.) vs conTENT (adj.) CONtent (n.) vs conTENT (adj.).

It seems that the noun is a CON, then, and the adjective is happy. But seriously, content-first, music second, as the new adage goes.

And you before either.

In her seminal essay, Against Interpretation (1966), Sontag calls for a return to a more primal appreciation of the aesthetic object, refusing to ‘explain’ the work away, diminish it, or reduce it to its political or ideological apparatus. We see this tendency to want to explain a piece of art play out whenever we walk into an art gallery or museum to be greeted with an audio guide or an interpretive panel rather than letting the works sink in.

The psychiatrist, writer, and former Oxford literary scholar, Dr Iain McGilchrist29, whose theory of the divided-brain hypothesis as relayed in The master and his emissary: the divided brain and the making of the Western world (2010), Against Criticism (1982), and the double totemic, The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World (2021), illustrates the dogma of left-brained hemisphere thought which he argues permeates institutions and ideological constructs. In brief, we can summarise his thesis, thus: left-brained hemispherical thinking = either/or; and right-brained = and/both.

McGilchrist speaks to the embodied over the abstract, reiterating the primacy of the body. In accordance with his theory, spontaneous song-making and improvisation would occupy the more expansive right-brain hemisphere, which is receptive and open to uncertainty, and states of ambiguity.

He draws upon extensive clinical practice and observation of brain-damaged patients to illustrate his points, focusing on how they use their hands after injury, for example. Patients suffering from right-brain deficit reach out to ‘grasp’ and control the world; whereas those with a left-brain damage will gesture outwards, extending their hand, rather than grasping. The right-brain hemisphere is concerned with ‘the bigger picture’. It lights up on brain scans when immersed in flow-states such as musical improvisation, or spontaneous song, composing, writing, and recording in-the-moment.

VII

What Makes Me Tick

I do, I undo, I redo.

- Louise Bourgeoise, cited in Tate (2016)30

The French artist and sculptor, Louise Bourgeoise, known for her unnerving vigour and wardrobe of dark, libido-driven (even incestual) interwoven narratives discusses ‘happiness’ and its role in in her work, in conversation with Frances Morris, director of Tate Modern.

The conversations goes thus:

FM: Is it unusual for you to make happy work?”

LB: … I transform hate into love. That’s what makes me tick.

‘Hate’ may be too strong a word for many, though. Or just not the right word. It leaves me uncomfortable. Nor do I think it factors into my work. But I could substitute it for various other emotions which do.

Yet the same can’t be said for ‘love’.

Love is love.

VIII

The Book of Falling Words

When a teenager, I was routinely baffled by my elders who offered the following advice: “Do what makes you happy,” coupled with a crumpled face.

Discombobulated by the connotative dimension of what they were saying, and their “spoken costume”31 (Tagg, 2013, p.360), I now get that what they were actually saying was: Whatever you do, don’t end up like me.

Do what makes you happy, then, or don’t. It’s not a reasonable ethics to live by though. When making art do we care about being happy? It’s not a factor, surely? I’m more looking for meaning.

Moreover, as Žižek (cited in Big Think 2012) asserts: “We don’t really want to get what we think we want” (00:54).32 Happiness can also tend to mask as a substitute for what we really want but cannot name (Phillips, 2013).33 We might convince ourselves that all we need is that new iPhone 15 in Midnight Blue by tomorrow morning, or else, whereas our real desires are unknown to us. So, we go about projecting them onto shiny objects, no sooner unwrapped, themselves, than bound for delayed obsolescence which we presume will make us happy, until they don’t. The ‘happiness industry’34 then, seems doomed. As Eagleton chides, “[t]he concept of happiness has moved from the private sphere to the public one” (2016).35 Moreover, in the reputational economy, extracted from gift exchange and naturalised by social media, it is only ever a proximal goal.

We tend to suffer from buyer’s remorse. We either carry on for likes, then, or we don’t. We do something else instead.

IX

Antidotes

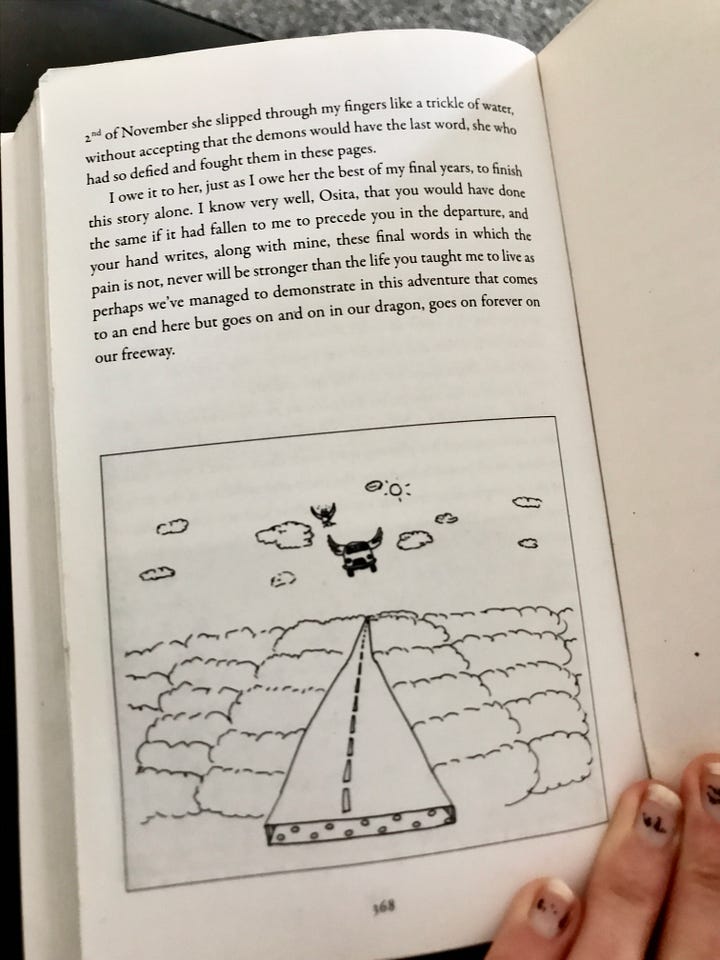

A literary antidote to much of the above is that of the Argentine author Julio Cortázar’s Autonauts of the Cosmoroute: A Timeless Route from Paris to Marseille (2008)36, an irreverent travelogue and love story written in collaboration with his second wife, Carol Dunlop, and originally published in Spanish in 1983 under the title Los Autonautas de la cosmopista: o Un viage atemporal Paris - Marseille.

Cortázar and Dunlop set out in their VW (called Dragon, in English) journeying for 33 days to get from Paris to Marseille on a route they had done times over, the imposition being that this time around they would allow themselves only two rest stops per day, the latter of which they would sleep at. Friends supplied provisions at meeting points along the way. Cortázar kept travel logs, which frequently interrupt the text. Theirs is a hymn to spontaneity and an antidote to much of the above.

The text is a melange of observations and an idea had and born out, a phenomenological exercise which was anything but convenient—blending slow nomadism, literary prose, autobiography, and photography, interspersed with offbeat drawings, fond anecdotes and much adoration. The duo’s anti-expedition (troubling the genre) is intimate in address, with the couple routinely calling one other by their pet names and inviting the reader into what I consider to be their rearrangement of time—revelling in imaginative daily rituals, over routine. This, Cortázar’s final book, is considered his happiest. The experience is saddened, though, on reading his postscript. Dunlop succumbed to illness not long after they’d completed the trip, and Cortázar himself died of cancer fifteen months later, in February 1984. Below, is a photograph of the postscript, written in December, 1982, complete with a drawing by illustrator Stéphane Hébert. Theirs is a call to “live, live more intensely” (2008, p.367). Cortázar wasn’t just writing, he was living.

Whilst it’s axiomatic that good writing necessitates paying attention to the world, as Simone Weil prophesied in her first book Gravity and Grace (1947). I knew from the outset that I wanted to be an artist who lived and breathed and fucked up and made up rather than one who wrote about living and breathing and fucking up and making up.

I'll give you my eyes, take me up, oh now please take me up

I'm helium raven waitin' for you, please take me up.

- Patti Smith “Birdland” Horses (1975)37

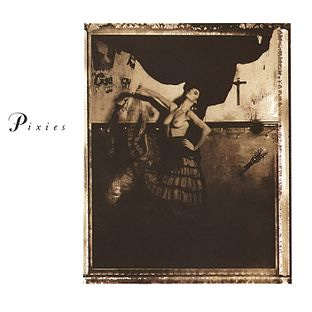

I had been in a significant relationship with a painter, ‘D’ who had ten years on me. He had previously introduced me to Cortázar one summer, amongst other things. Prior to meeting me, D had been in love with a Spanish girl from Bilbao. Her name was Rosa. (As women, we always compare, and imagine, and how could I possibly compete when she was named after the most beautiful of flowers?!) Regardless, Rosa had, at some point, given D a CD of The Pixies’ Surfer Rosa38 which was a revelation to me on hearing it one stolen evening but also for the cover art alone.

And D would hardly have come across it otherwise. So, in a sense, it was Rosa, a woman I had never met, only pictured, and not D that was my point of entry not only to The Pixies but also to Cortázar’s Hopscotch (1966). Such is the life of objects.

One morning, D was leaving for work. I was wrapped in a towel (young and beautiful, but not knowing it) when he me a book off the shelf.

“What do you mean I can read it any way I like?” I called out after him but there was no reply.

The book in question was Cortázar’s Hopscotch (1966), a stream-of-consciousness, and the first hypertext novel. It was written in Paris and originally published as Rayuela (1963) in the Spanish. Mine was the Panther version, below. The cover was rough to the touch and the muted browns and creams in its design matched D, somehow.

Gauging that there were roughly three ways I could read this book: 1) in order, 2) by hopscotching or 3) however I liked, I tried the second, expecting to come to an epiphany of sorts, but no. What Cortázar was teaching me (unbeknownst to me, at the tender age of 23) was that life lay within the flicking of the pages, and my own re-routing of the narrative—I could go anywhere in this book, and I would.

Intrigued by there being no particular ending to this story but any number of endings, or no ending at all, only possibility or a recursive loop, I got the inkling that authorial unruliness suited me just fine. Admittedly, there was a ‘Table of Instructions’ to read the first part in a linear fashion up until Chapter 56 and to then embark upon the second half via Chapter 73 but, I ignored this too.

X

Auras and midnights

In his seminal text, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (2008[1935])39, Walter Benjamin alerts us to the “aura” (uniqueness) of an artwork. Moreover, in Understanding Brecht, Benjamin reinforces the role of “The Author as Producer” (1998)40, by bringing us back to the social imperative of the artwork, in that: “the rigid, isolated object (work, novel, book) is of no use whatsoever. It must be inserted into the context of living social relations” (p.87).

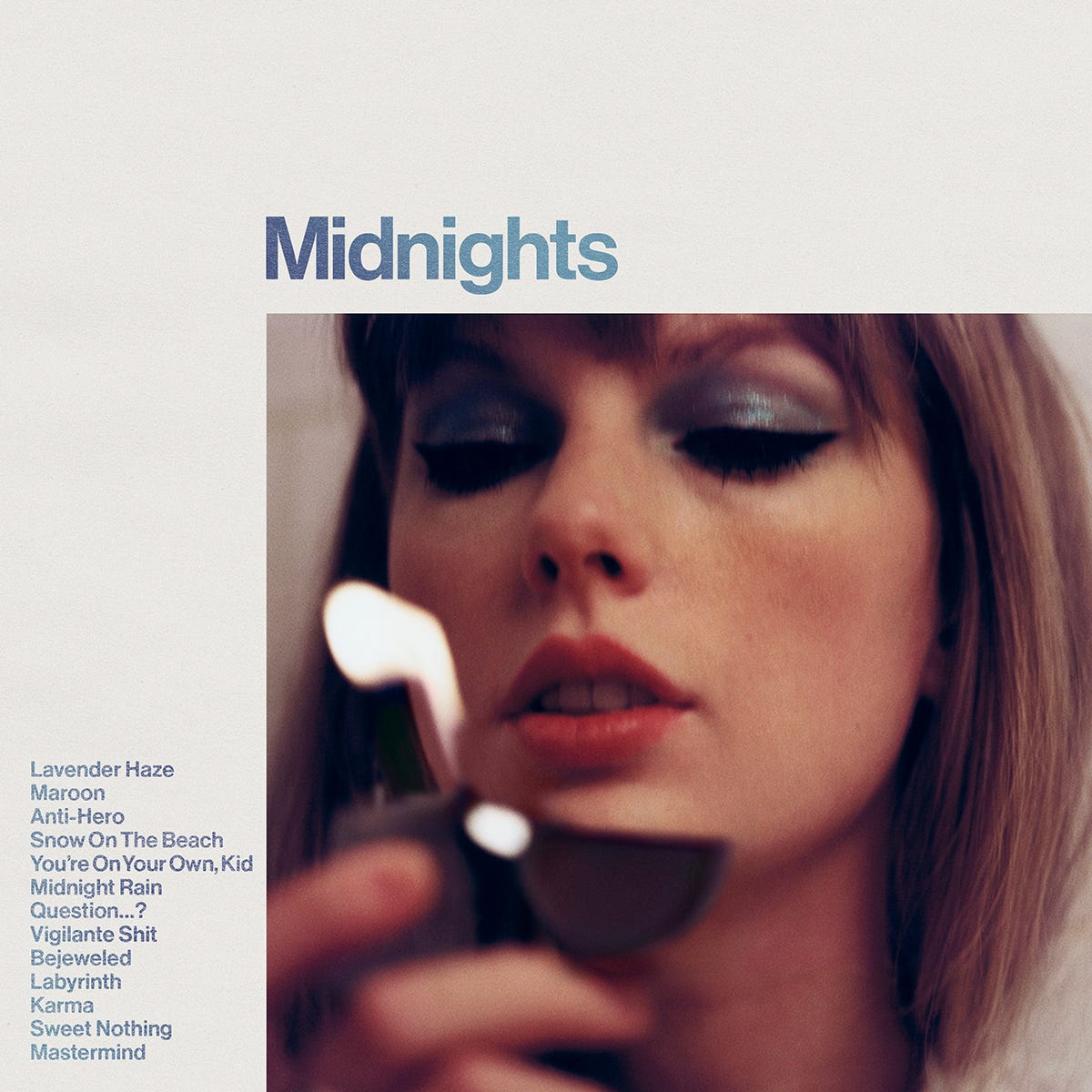

When I last stayed over at my brother’s, there was a vinyl copy of Taylor Swift’s Midnights sat on the top shelf of the spare room in which I was sleeping.

It is a beautiful object, admittedly, with Swift’s kohl make-up, and downcast eyes, curled with noir liquid liner. She’s holding a lighter, with an eternal lick. We know she doesn’t smoke, but we don’t care. She looks good. Lonely midnight blues and introspection. We’ve all been there. Her mouth; expectant. The gradation of powdery blue letters. The off-kilter angle of the flame, immortalised.

Surpassing the aura of the Midnights41 album cover, are, though, perhaps, the sparkly Eras Tour sets and magnificent costume changes, in between which stages are lit up and transformed into rapturous fairy tales.

This brings me to the GRAMMYs 2024 best single being awarded to Miley Cyrus’s “Flowers” over Lana Del Rey’s A&W (original title, “American Whore”). When I brought up ‘Del Rey vs Swift’ recently with a friend, he asked: “But who would you rather go out to dinner with?” Del Rey would either stand you up, or leave you lingering too long over a naked Negroni or two, before summoning the waitress, and implementing some moody pirouetting, whilst pontificating over the lack of real men left in this God forsaken world—but still, I’d take her over Swift any day, and see where it led me.

XI

Body Electric

Lana Del Rey’s 2012 rendition of “Body Electric” from her critically acclaimed album Born to Die (2012): The Paradise Edition (Special Version) performed with a live orchestra at BBC Radio 1’s Hackney Weekend in 2012 (Sebastian Isla, 2012)42 is a pounding meditation on desire.

The vacuity of her stare is intoxicating in contrast to the lyrical denotations. Then we have her teetering, and kneeling, in her tulip red dress, toying with the microphone stand, in hand. Then there is her voice, rising and falling, dripping and balling, all over the stage: a Dionysian delight.

In The Birth of Tragedy (1872), Nietzsche draws upon The Greek Tragedies to distinguish between the two opposing forces: the Apolloline and the Dionysiac, demarcating their necessary role and merger in the creative act: Übermensch - the will to power - and a template for our better selves. Nietzsche believed in the affirmatory properties of art, in that the aesthetic is justification of the power that art can play in re-affirming life, than in art, per se.

In his preface to The Gay Science (2001, p.3), Nietzsche writes, rather wondrously, of a: “sudden sense and anticipation of a future, of impending adventures, of reopened seas, of goals that are permitted and believed in again.”43 Is this not what art does for us, repeatedly?

In 2019, after a relationship ended, I began a series of poems called My Spiritual Cowboy, which resides on my Google Drive and which I have long since put to bed. Touch—the most precious of auras. Below, is a poem I wrote at the time.

“Intimacy” (2018)

A waterfall haunts my neck. Pummelling things said. Orange blossom bubbles trail my neck. The shower—fixed— retains a constant temperature. Some people need drama in order to exist, so they create it. I sit in a pool. Algae tide like flash- backs. A lily pad flannel, floats. All we can do is itemise things. Lost soap—swirl— my hand. Chase— a bar of gold.

Fisher has this line on ideology, as being: “the form of dreaming in which we live” (2016, 00:25:02).44 Lucid, even poetic. Besides, who else would have put it that way?

XII

On walking down escalators backwards

The other day on drafting this, my sister texted to let me know it was World Happiness Day, and I didn’t even know! Ta-da! From quantified selves to Mr. Men, let’s lighten things up a bit around here, then.

Remember Roger Hargreaves’s series? My early Dionysian tendencies may have already been assured as Mr. Happy simply bored me! All that happiness! What could be more boring? If I had to go out to dinner with one of these chaps, it wouldn’t be him. So who would I pick? Mr. Tickle? Dinner would certainly be interesting. But what about Mr. Bounce or Mr. Messy? Mr. Greedy or Mr Jelly? Fun, perhaps, but my dream dialectic would have to be Mr. Rush and Mr. Daydream, imagine that?

This brings me to autumn 2002. I was living in an art studio opposite Nottingham train station with a bunch of creatives all paying around £35 a week for a room. There were no shower facilities so we used buckets, washed in the sink or used the gym instead. I rented this massive, white space. In it was a table, a chair and a full-length, stand alone mirror.

I spent one afternoon positioning cacti plants around the edges of the room and photographing it—transforming it into a vast white desert.

D got the train up to see me. We argued, and he got the train back down then turned around mid-transit. I had taken some nudes of me stood before the mirror and put them loose in the drawer. When he’d gone, so had they. He swore he hadn’t taken the nudes.

I’d been sewing sheets of toilet paper into a massive quilt for an art exhibition. It was spilling over the desk, carefully sewed paper, the juxtaposition of thread and pulp.

I had to get a job so I took a temporary seasonal position at Nottingham Waterstone’s. Once ensconced on the travel floor, I became aware of a funny chap who worked there. He had a laconic Antipodean drawl and took to calling me up from the third floor.

“Good morning, Samantha.”

He then took to calling me up whenever he wasn’t doing anything of importance and even when he was. One time, he walked down the escalator to talk to me.

On his holiday, he took a whistle-stop tour of European cities and every other day a new postcard or a photograph defaced with handwritten marker pen with absurd and playful messages of devotion landed on the mat. They were always signed: “Yours,...”

I’m now reminded of this prompt on dating apps, that asks: “What is the most unusual gift you’ve ever received?”

One morning, on my way into work, I was walking up Clumber Street when I looked up and saw a GIANT hand drawn MR. TICKLE. Its arms were spread across the vertical glass window from the second to the seventh floor and last week, a strange thing happened. The same voice that would ring me up from the third floor and routinely banish my boredom fell into my ear via a Penguin promotional video in a The Guardian review on a set of new biographies on the Australian artist Frank Moorhouse. When my precarious contract as a bookseller came to an end, I found an unopened and complete box of Mr. Men books mysteriously housed in my locker.

Postscript

With thanks to Jer Reid, Graham and Ray at GIOdynamics for this footage. 27/3/24.

“I Sing the Body Electric” is a poem by Walt Whitman, first published without a title in Leaves of Grass (1855 edition), re-published in 1856 under the title Poem of the Body, and acquiring its present title in 1867. It is a paean to the human body and its desires, and manifestations of soundness, uniting body and soul. At the time of writing, the word ‘electric’ was not commonly cited.

Whitman, W. 1998. The Project Gutenberg eBook of leaves of grass, by Walt Whitman. [Online]. [Accessed 23 March 2024]. Available from: https://gutenberg.org/files/1322/1322-h/1322-h.htm#link2H_4_0030

Cortázar, J. and Dunlop, C. 2008. Autonauts of the cosmoroute: A timeless route from Paris to Marseille. Translated by A. Mclean. London: Telegram Books.

Berardi, F. 2009. The soul at work. From alienation to autonomy. Translated by F. Cadel and G. Mecchia. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Graeber, D. 2018. Bullshit jobs. London: Simon & Schuster.

Cave, N. 2023. Issue #218. The Red Hand Files. [Online]. [Accessed 29 January 2024]. Available from: https://www.theredhandfiles.com/chat-gpt-what-do-you-think/

In this response to a reader of The Red Hand Files, Cave relays his opinion on songs written by ChatGPT ‘in the style of Nick Cave’.

Also, see:

Scarlett, L. 2024. Nick Cave was sent an AI track written 'in the style of Nick Cave', and he's distinctly unimpressed: "This song sucks". Loudersound. 17 January. [Online]. [Accessed 17 February 2024]. Available from: https://loudersound.com/news/nick-cave-was-sent-an-ai-track-written-in-the-style-of-nick-cave-and-hes-distinctly-unimpressed-this-song-sucks

Suno AI. 2024. Suno AI’s website. [Online]. [Accessed 25 August 2017]. Available from: https://suno.com

Talbot, S.L. 2023a. Forever chemicals. Sam Lou Talbot. Space junk. [Online]. Glasgow: Sam Lou Talbot.

Cci collective. 2016. All of this is temporary: Mark Fisher. [Online]. [Accessed 10 December 2021. Available from: https://youtube.com/watch?v=deZgzw0YHQI

Wu, T. 2016. The attention merchants: The epic scramble to get inside our heads. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Hyde, L. 1983. The gift: imagination and the erotic life of property. New York: Vintage.

James, W. 1891. The principles of psychology. London: Macmillan and Co.

Sam Lou Talbot. 2020. Zoom to God. [Online]. [Accessed 11 November 2020]. Available from: https://youtu.be/dALFoRlJtTs?feature=shared

Han, B. 2015. The burnout society. Translated by E. Butler. CA: Stanford University Press.

Han. B. 2017. Psychopolitics, neoliberalism and new technologies of power. Translated by E. Butler. London: Verso.

Binyam, M. 2022. You pose a problem. A conversation with Sara Ahmed. The Paris Review. [Online]. [Accessed 29 March 2024.] Available from: http://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2022/01/14/you-pose-a-problem-a-conversation-with-sara-ahmed

McClary, S. 1991. Feminine endings: music, gender, and sexuality. Minnesota, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Herzog, W. 2023. Every man for himself and God against all. A Memoir. Translated by M. Hoffman. London: Vintage.

Prager, B. 2007. The cinema of Werner Herzog: aesthetic ecstasy and truth. London: Wallflower.

Grubbs, D. 2014. Records ruin the landscape: John Cage, the sixties, and sound recording. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Talbot, S.L. 2023i. Glory skin. Sam Lou Talbot. Space junk. [Online]. Glasgow: Sam Lou Talbot. [Accessed 25 October 2024]. Available from: https://samloutalbot.bandcamp.com/track/glory-skin

Atlantic. 2017. David Lynch on where great ideas come from. [Online]. [Accessed 30 March 2020]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mFsBaa_MEzM

Sam Lou Talbot. 2023f. The land of nod. [Online]. [Accessed 10 September 2023]. Available from: https://youtu.be/qBoZQCrKbRw?si=35zyGagSodNjS4MM

Shklovsky, V. 1917. Art as technique. [Accessed 4 April 2024]. Available from: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/fulllist/first/en122/lecturelist-2015-16-2/shklovsky.pdf

Morgan, S. and Jonas, J. 2006. Joan Jonas: I want to live in the country (and other romances). London: Afterall Books.

Calle, S. 1981. The hotel, room 47. [Online]. [Accessed 26 March, 2024]. Available from: www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/calle-the-hotel-room-47-p78300

Calle, S. 1979. Suite Vénitienne.

Han, B. 2020. The Disappearance of rituals: A topology of the resent. Translated by D. Steuer. Cambridge: Polity Press.

James, L. 2018. Semantic satiation. What happens when you repeat a word over and over again. [no place]: independently published.

McGilchrist, I. 1982. Against criticism. London: Faber.

McGilchrist, I. 2019. The master and his emissary: the divided brain and the making of the Western world, 2nd ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Online]. [Accessed 19 March 2022]. Available from: https://go.exlibris.link/9TrHq9vw

McGilchrist, I. 2021. The matter with things: our brains, our delusions, and the unmaking of the world. London: Perspectiva Press.

Tate. 2016. Louise Bourgeois: ‘I transform hate into love'. Take an intimate look at the life and work of the French artist. [Online]. 3 June. [Accessed 15 March 2024]. Available from: http://tate.org.uk/art/artists/louise-bourgeois-2351/louise-bourgeois-transform-hate-love

Tagg, P. 2013. Music's meanings: a modern musicology for non-musos: "good for musos, too". New York: The Mass Media Music Scholars' Press.

Tagg (2013, p.360) states “Vocal costumes” are those we put on “like clothes”.

Big Think. 2012. Slavoj Žižek. Why be happy when you could be interesting? Big Think. [Online]. [Accessed 20 August 2023]. Available from: http://youtu.be/U88jj6PSD7w

Phillips, A. 2013. On missing out: In praise of the unlived life. London: Picador.

Davis, W. 2015. The happiness industry: How government and big business sold us well-being. London: Verso.

Eagleton, T. 2016. The happiness industry by William Davies review – why capitalism has turned us into narcissists. The Guardian. [Online]. 3 August. [Accessed 20 March 2024]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/aug/03/the-happiness-industry-by-william-davies-review

Cortázar, J. and Dunlop, C. 2008. Autonauts of the cosmoroute: A timeless route from Paris to Marseille. Translated by A. McLean. London: Telegram Books.

Patti Smith. 1974. Horses. [CD]. US: Arista Records.

Pixies. 1998. Surfer rosa. [CD]. London: 4AD.

Benjamin, W. 2008. The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. London: Penguin.

Benjamin, W. 1998. The author as producer. Understanding Brecht. [Online]. Translated by A. Bostock. London: Verso. [Accessed 22 October 2024]. Available from: https://yaleunion.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Walter_Benjamin_-_The_Author_as_Producer.pdf, pp.85-103.

Taylor Swift. 2022. Midnights. [Vinyl]. New York: Republic Records.

Sebastian Isla. 2012. Lana Del Rey. Body electric. (Live at BBC Radio 1’s Hackney weekend. June 24, 2012. [Online]. [Accessed 20 July 2023]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VGezT1gxE-A

Nietzsche, F.W. 2001. The gay science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cci collective. 2016. All of this is temporary: Mark Fisher. [Online]. [Accessed 10 December 2021]. Available from: https://youtube.com/watch?v=deZgzw0YHQI

This post is pure gold. So much to unpack. Thank you.

Brilliant essay. Thought-and-feeling provoking. Many, many resonances with my own influences and heroes. (And I also walked the Camino Portugues last year, though without an amp on my back, and only from Ponte de Lima, where I live.) May I offer one tiny correction? I hope you won't think I'm nit-picking--but it's the over-reliance on left-hemisphere thinking that McGilchrist laments so rightly in our society. Believe it or not, literally moments before I read your essay my eyes had grazed my copy of Hopscotch, which I've started several times but never finished (in any direction), and thought: I really must have another go at that. Synchronicity? I think so.